DAUBISM - available works

Welcome to the Daubism Shop

Every work available here is part of Driller Jet Armstrong’s ongoing transformation of the Australian landscape painting tradition. Each piece begins with an existing or forgotten landscape — a relic of another painter’s vision — and is revived, altered, and reimagined through the Daubist process.

From subtle interventions to radical reconstructions, these works celebrate the spirit of reinvention: playful, provocative, and deeply Australian.

These are not reproductions or prints.

Every artwork is a one-off object, carrying both its original painter’s history and its new Daubist identity.

For purchases or enquiries, please contact: drillerjet@me.com

The Butterfly Effect (1996)

45 × 56 cm

Medium: Atticus Atlas Butterfly wings attached to an original landscape painting

Price: $5,000.00

The Butterfly Effect is a fully realised Daubist artwork from the mid-1990s, in which Armstrong disrupts a conventional Australian landscape by physically intervening with real butterfly wings. Their placement transforms a dead tree into a strange, living creature—part sculpture, part painting, part rebirth.

Here, the Daubist act is unmistakable: an inherited image is opened up, altered, and re-authored. The butterfly wings refuse passivity; they become agents of metamorphosis, unsettling the sentimentality of the original landscape and asserting Armstrong’s signature strategy of appropriation, collision, and renewal.

A striking and early exemplar of Daubism’s radical gesture.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

Unicorn by a Billabong Lets One Rip (2020)

H 51 cm x W 61 cm

Felt cut-out and acrylic additions on original landscape painting

Price: $$1500.00 (AS AT 2025)

In this key work from the Unicorn Felt Series, Driller Jet Armstrong inserts a pop-culture mythological creature directly into the Australian bush — then gives it permission to behave exactly as the internet insists it must. The unicorn stands by a quiet billabong, framed by earnest colonial-era trees, and casually releases a rainbow into the landscape.

This hilarious collision of earnest Australiana and hyper-saturated meme culture is classic Daubism: irreverent, celebratory, and absolutely uninterested in treating inherited imagery as sacred. The felt unicorn is deliberately naive, almost toy-like, amplifying the absurdity of the scene while pointing to the way contemporary culture overlays itself — loudly and nonsensically — onto inherited visual traditions.

A standout example of Armstrong’s long-running practice of “resuscitating” found paintings by inserting new cultural signals into their surfaces.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

BOY ON A BENCH WITH A BALL (2010)

49 × 44 cm

Medium: Felt cutouts on original landscape painting

Price: $2,200.00

A quietly subversive Daubist intervention. Onto a traditional Australian landscape, Armstrong introduces a felt-cutout boy, perched on a bench with his basketball — an intrusion that is both playful and destabilising. The felt figure refuses to assimilate into the inherited scene; instead, it ruptures the painting’s original intent and asserts a new narrative, authored through Daubism’s signature act of purposeful interruption.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

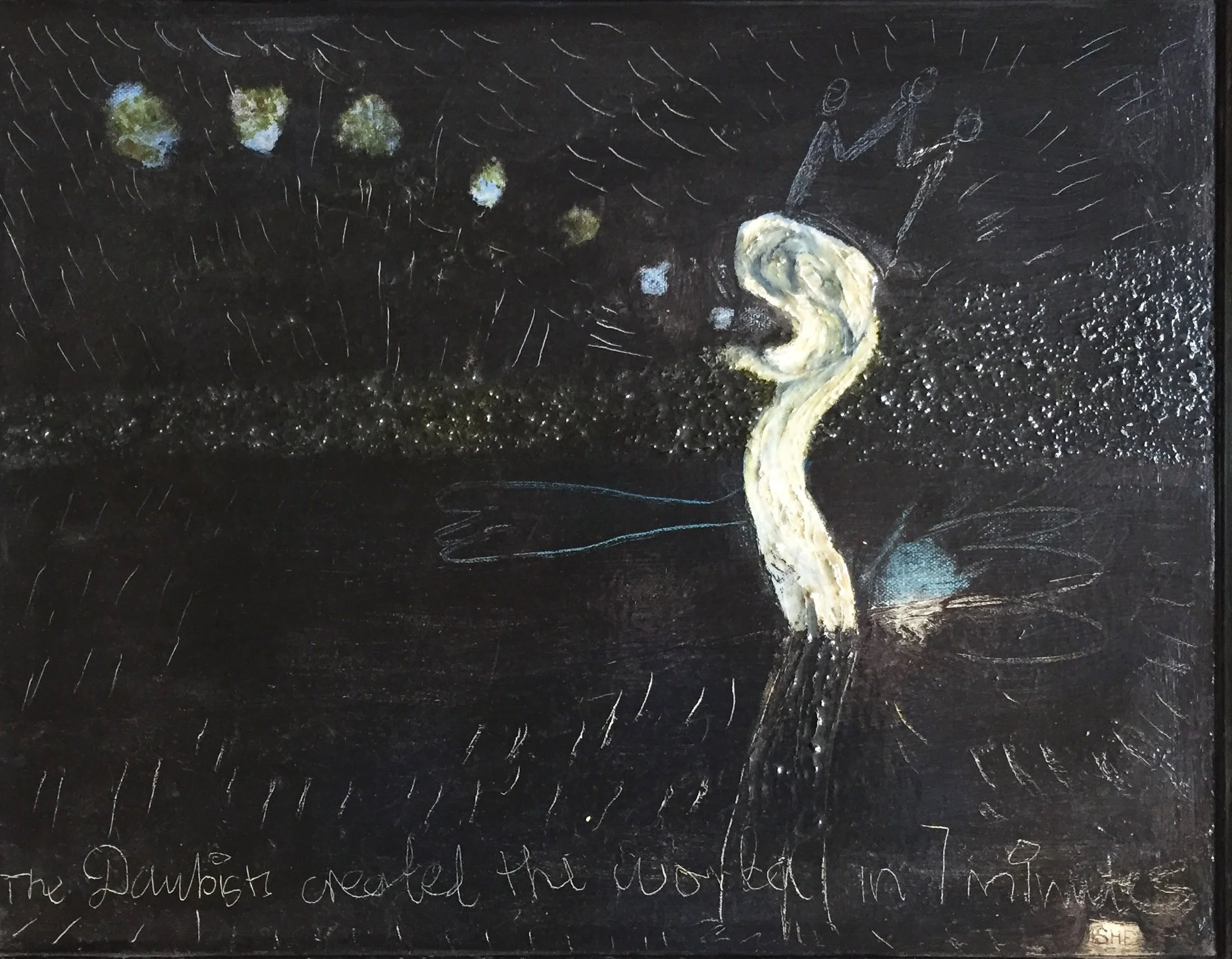

Daubist Creation (2020)

acrylic on original landscape painting.

$3000.00

Daubist Creation explores the moment before form becomes matter. Emerging from a field of darkness, a luminous figure rises—part question, part genesis—suggesting the birth of a world shaped not by certainty, but by instinct and gesture. Marked by textured strokes, drifting light, and cosmic stillness, the work invites the viewer to witness creation as an act of intuition rather than design.

Daubist Bottle (1995)

78 × 50 cm

Medium: Torn landscape painting on paper, reassembled and mounted; framed behind glass.

Price: $5,500.00 (change anytime)

One of the earliest fully resolved Daubist works, Daubist Bottle marks a pivotal moment where Armstrong began to dismantle an artwork literally and conceptually. The original landscape painting — torn apart, reassembled, and reoriented — becomes the unstable ground upon which the new image is built.

The bottle form is fractured, architectural, almost cubist in its reconstruction. What once depicted a conventional view is now an object with memory scars, rearranged into a new visual logic. This work demonstrates the fundamental Daubist principle: authorship is not added but reconfigured.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

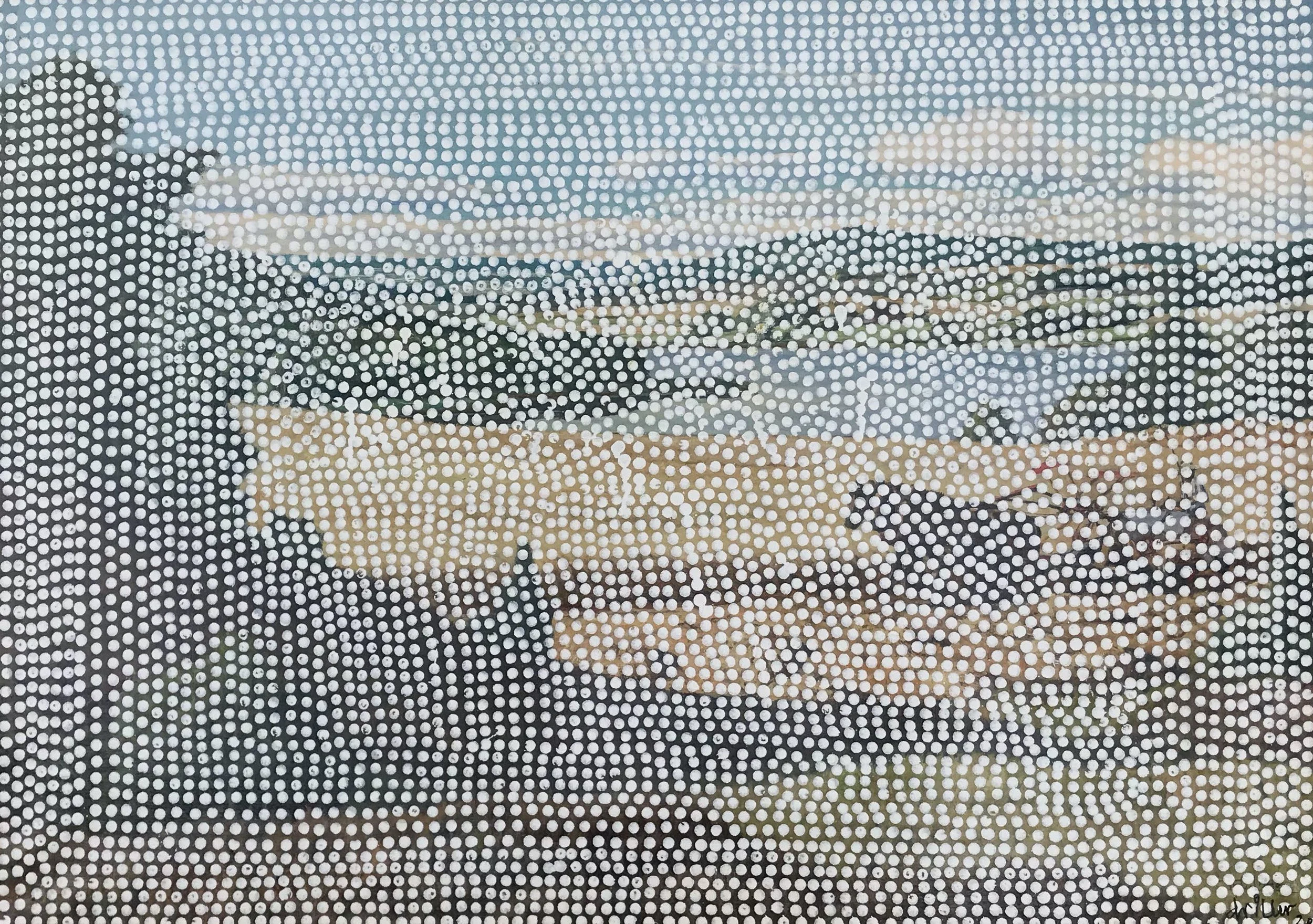

Spot Painting #1 (2020)

85 × 120 cm

Medium: Acrylic dot intervention over original landscape painting

Price: $6,500.00 (adjust anytime)

Spot Painting #1 is one of the most recognisable Daubist works of the last decade — a direct, pointed dialogue with both Western landscape painting and the commodified language of contemporary art.

Armstrong overlays the inherited pastoral scene with a dense field of hand-painted dots, creating a shimmering veil that simultaneously reveals and obscures the image beneath. Unlike mechanical patterning or appropriation-as-quotation, these dots are insistently human, rhythmically imperfect, the labour visible in every mark.

The work interrogates authorship and authenticity from multiple angles:

– the original artist’s landscape remains visibly present

– Armstrong’s intervention asserts a second authorship

– the dots evoke the aesthetics of First Nations art while deliberately avoiding any stylistic mimicry, thus raising questions about cultural influence, ownership, and the ethics of mark-making in Australia.

This is Daubism at its most distilled: a collision of histories, aesthetics, and hands — one painting becoming two, becoming something else entirely.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

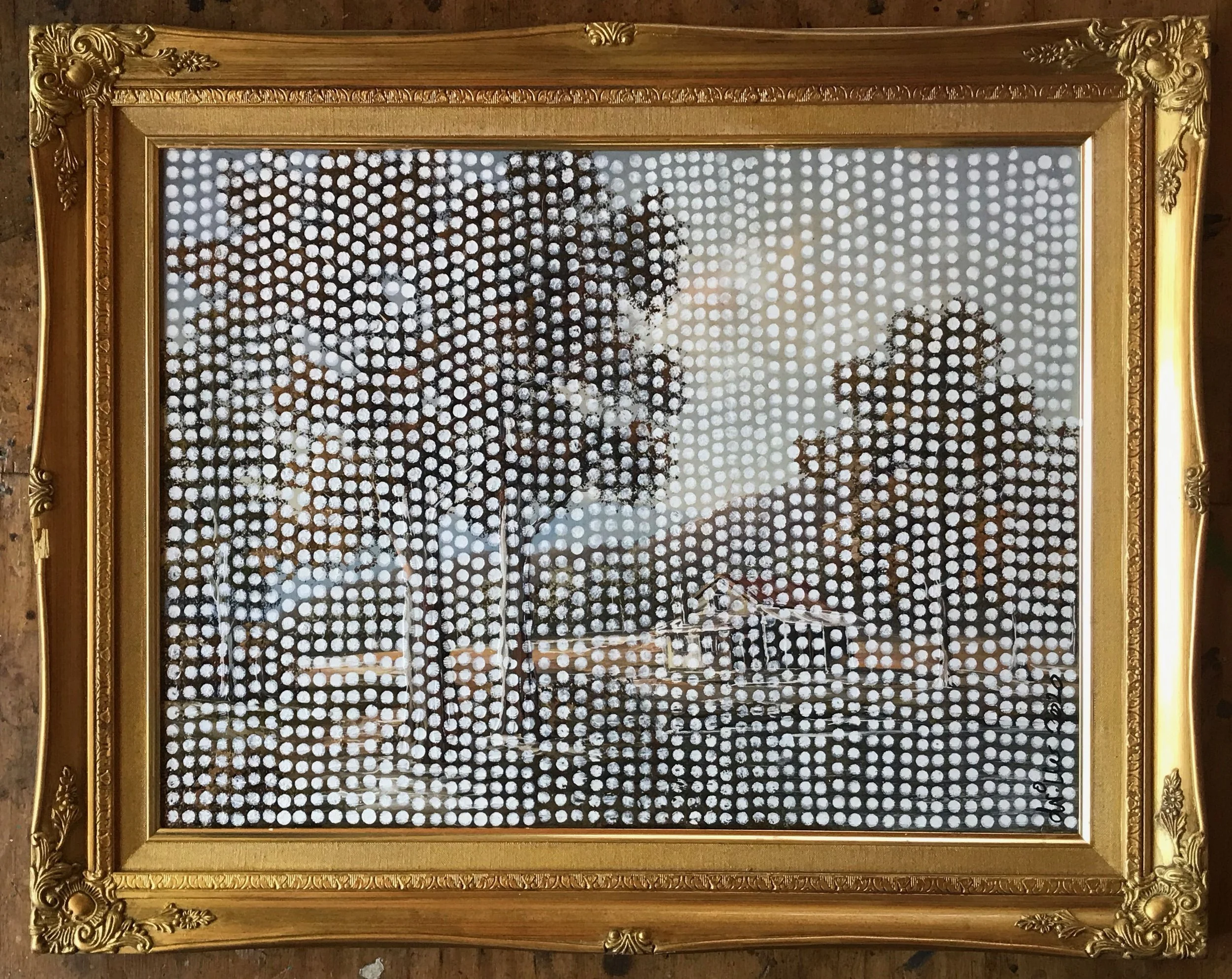

Spot Painting #3 (2020)

60 × 72 cm

Medium: Acrylic dots over original landscape painting

Price: $2,200.00

Spot Painting #3 continues Armstrong’s Daubist interrogation of the inherited Australian landscape. A quietly nostalgic rural scene becomes charged and contemporary through a dense field of hand-applied acrylic dots.

The intervention operates like a screen or membrane — half-revealing, half-concealing — turning the original painting into something simultaneously familiar and estranged. The image beneath feels as if it’s flickering, trying to break through a coded surface.

Unlike mechanical repetition, each dot is deliberately imperfect, signalling presence, rhythm, and the human hand. In this work, the dots act almost like digital pixels imposed onto an analogue past, transforming the landscape into a site of interference, translation, and re-authorship.

A refined, smaller-format Daubist piece, Spot Painting #3 is both accessible and conceptually potent — a key example of Armstrong’s ongoing exploration of multiplicity, authorship, and the life of inherited images.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

Daubist Corgi with Queen (1992)

H 150 cm x W 102 cm

Medium: Cut and reassembled Charles Bannon landscape painting

Price: $10,000.00

An early and definitive Daubist masterpiece, Corgi with Queen demonstrates Armstrong’s radical method at full power: the original Charles Bannon landscape has been meticulously cut, rearranged, and reanimated into a new narrative—one that merges humour, monarchy, and the unmistakable larrikin spirit at the heart of Daubism.

This work sits inside the pivotal moment of public controversy and cultural debate that helped define Armstrong’s career. It is bold, irreverent, and unapologetically transformative—a landmark statement in the evolution of Australian appropriation art. enquire at drillerjet@me.com

First Australian in Europe (2021)

H 55 cm × W 64 cm

Medium: Painted addition to original landscape painting

Price: $3,000.00

Description:

In this sharply humorous Daubist intervention, a serene European riverside scene becomes the unlikely stage for a bold Antipodean arrival. Armstrong overlays the inherited landscape with a stark, glyph-like figure—part traveller, part ancestral echo—interrupting the borrowed idyll with unmistakable Australian presence. The work playfully critiques colonial narratives of “arrival” by reversing the gaze: here, Europe becomes the backdrop onto which Australia projects itself.

A quintessential example of Daubism’s central gesture—reclaiming, rewriting, and recharging second-hand imagery—this painting fuses wit, critique, and visual punch in a single, declarative mark.

enquire at drillerjet@me.com

Hans Heysen Daub (2022)

H 51 cm × W 65 cm

$2,500.00

Medium: Gel-medium image transfer layered onto an original landscape painting.

The transferred gum trees—lifted from a Hans Heysen image—float ghost-like across the inherited landscape, creating a doubled vision of Australian pastoral mythmaking. The work folds one canonical painter into another, a literal and conceptual overlay that embodies Daubism’s challenge to authorship, value, and “official” images of the land.

Enquiries & purchase:

📧 drillerjet@me.com

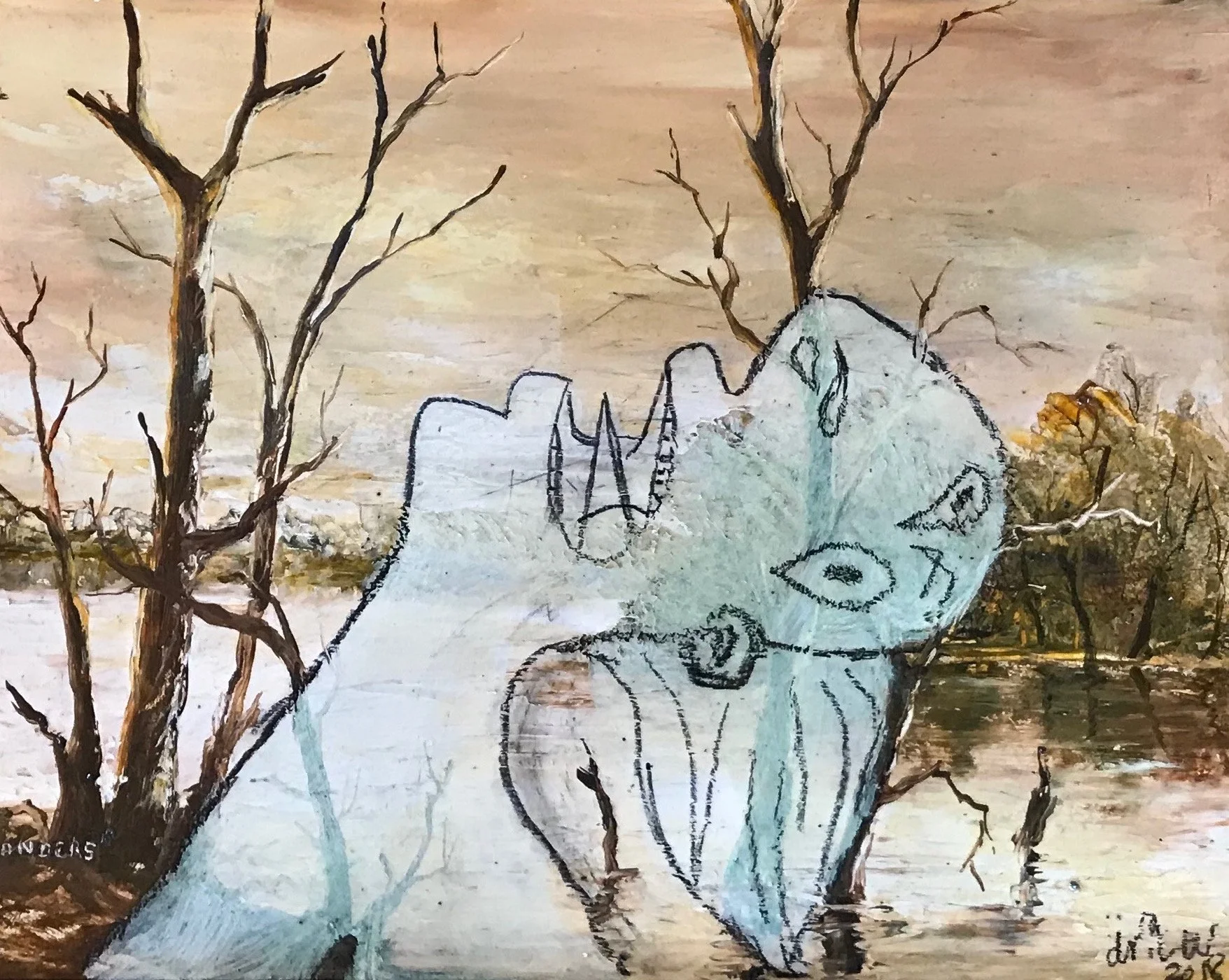

Her body was found in the river (2018)

H 50 cm × W 61 cm

$3000.00

Medium: Painted Picasso-inspired intervention over an original landscape painting.

A quiet river scene ruptures under the apparition of a fragmented, blue-toned figure — a ghostly Picasso form laid over the colonial landscape like an accusation. The work stages a confrontation between European modernism and the Australian pastoral imaginary, turning the river into a site of unease, memory, and unresolved narrative. Classic Daubism: slipping two art histories together until they grind and spark.

Enquiries & purchase:

📧 drillerjet@me.com

Jarjum (2020)

H 60 cm × W 75 cm

$2,200.00

Medium: Gel medium transfer over an original landscape painting.

A spectral child figure — silhouetted, solid, unignorable — is placed into a misty colonial landscape that was never painted for him. Jarjum (Bundjalung word for “child”) turns the sentimental bush scene inside out: the land is no longer a neutral backdrop but a site of presence, sovereignty, and memory. The Daub becomes a correction, a truth-telling intervention that refuses erasure.

Enquiries & purchase:

📧 drillerjet@me.com

Landscape as an Abstract Concept (2023)

H 95 cm × W 70 cm

Price: $5,500.00

Medium: Original landscape paintings cut, reassembled, and overpainted

Description:

Landscape as an Abstract Concept is a major Daubist work in which traditional landscape paintings are literally dismantled and reborn. Each fragment of the original landscapes is cut, repositioned, and recontextualised, creating an intricate mosaic of Australia’s visual memory. The bold black connective lines unify these shards into a new, pulsing composition — part cartography, part archaeology, part resurrection.

This work embodies the core Daubist gesture: acknowledging the lost, forgotten, or discarded landscape painting and granting it a new, contemporary agency.

A statement piece for collectors who understand that Australian art history is not static — it is something to be cut up, remixed, challenged, and revived.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

Whale Watching #23 (2018)

H 61 cm x W 75 cm

Painted addition and googly eye on original landscape painting

Price: $2,500 (as at 2025)

A rare surviving piece from Driller Jet Armstrong’s sought-after Whale Series, Whale Watching #23 stages an enormous, deadpan black whale surfacing into an otherwise sentimental rural landscape. The original painting — calm, decorative, innocently picturesque — is abruptly interrupted by the matte monolith of the whale’s body, its lone googly eye staring back with mute indifference.

The collision between charm and absurdity is the point: a quiet reminder that landscapes are never neutral, and that the Australian tradition of pastoral escapism is ripe for disruption. With one bold gesture, the work transforms the genteel riverbank into a site of humour, drama, and conceptual friction.

A classic example of Armstrong’s Daubist strategy: take a painting that has nothing left to say, and give it something to talk about.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

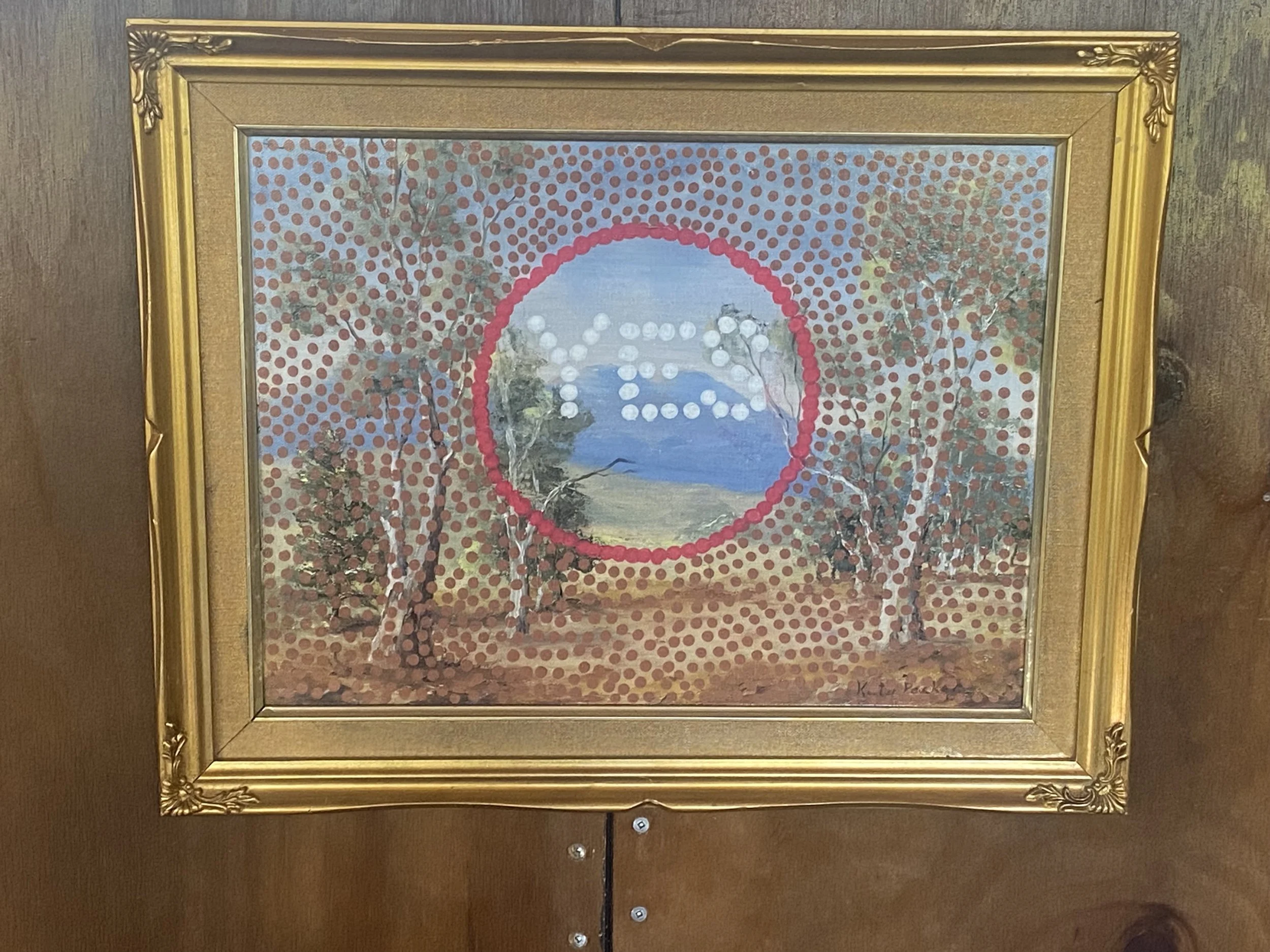

Yes to the Voice Daub (2023)

H 40 cm x W 50 cm

Acrylic dots and painted intervention on original landscape painting

Price: $1,500.00

Created in the same year Australians voted on an Indigenous Voice to Parliament, Yes to the Voice Daub transforms a nostalgic bush landscape into a site of national reckoning. A ring of red and brown dots — echoing both desert iconography and colonial halftone printing — surrounds a central “YES,” rendered in stark white acrylic dots.

The original landscape attempts its usual trick: to soothe, to distract, to pretend history is a gentle, untroubled thing. Armstrong refuses the illusion. The intervention punctures the idyll, insisting on visibility, agency, and the weight of the moment.

Part political poster, part cultural remix, the work is a concise example of Daubism’s ethos:

take the inherited image, and make it speak.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

Welcome to Country (2019)

H 51 cm × W 61 cm

Acrylic intervention on original landscape painting

Price: $2,200.00 (2025)

In Welcome to Country, Armstrong overlays a conventional river-scene landscape with a bold, ochre-filled geometric form edged in delicate white dots — a direct homage to the visual language pioneered by Gija artist Rover Thomas. The work doesn’t imitate cultural content; instead, it recognises how Thomas transformed Australian art by asserting Country itself as the central subject.

Against the soft, sentimentalised backdrop of colonial landscape painting, Armstrong’s intervention sits like a truth-telling device: a shape that refuses to vanish into the scenery, a presence that insists on being seen. It disrupts the illusion of an empty, ownerless land and acknowledges the sovereignty and ongoing cultural memory carried by Country.

A quietly powerful Daubist statement, the work reframes the landscape not as a postcard, but as contested ground — layered, lived in, and never neutral.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

Lutana (in the sky with diamonds) (2016)

H 47 cm × W 60 cm

Posca on original landscape painting

Price: $1,800.00

In this work, Armstrong releases a luminous, airborne figure — Lutana — across the surface of a subdued Australian landscape. Drawn in bright white Posca lines, the figure floats horizontally like a cosmic visitor or a spirit mid-ascension, scattering star-shaped symbols across the sky.

The Daubist gesture is playful, psychedelic and otherworldly, invoking the dreamlike optimism of Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds while also unsettling the quiet colonial scene beneath. Armstrong’s figure acts as a joyful disruption: a reminder that the landscape is never empty, never inert, never without presence or story.

Softly anarchic and gently cosmic, Lutana continues Armstrong’s commitment to re-enchanting the Australian landscape through layered authorship, humour, and deliberate intervention.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

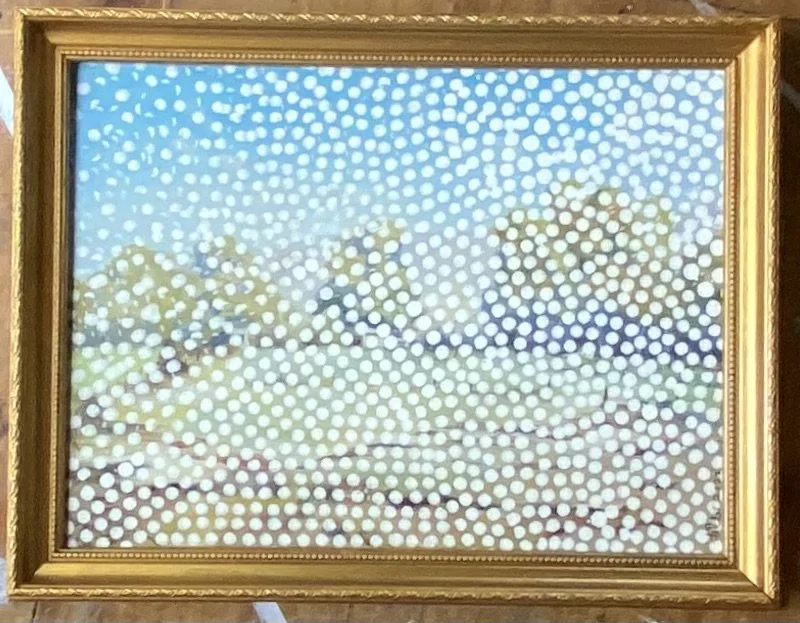

Spot Painting #12 (2023)

H 38 cm × W 49 cm

Acrylic dots on original landscape painting

Price: $1,200.00

In Spot Painting #12, Armstrong applies a dense veil of white acrylic dots across a softly rendered pastoral landscape, dissolving depth and flattening the scene into something shimmering, rhythmic and pixelated.

The work continues his acclaimed Spot Paintings series, where the artist interrupts and reclaims inherited landscape imagery by overlaying it with thousands of deliberate, repetitive marks — part sabotage, part sanctification. The dotted field becomes a kind of optical interference pattern, simultaneously obscuring and illuminating the landscape beneath.

Playful, methodical, and unmistakably Daubist, this piece demonstrates Armstrong’s ongoing commitment to disrupting the colonial gaze through gesture, humour, and sheer accumulation.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

Black Hole (2019)

H 58 cm × W 78 cm

Daubist addition to original landscape painting

Price: ($2500.00)

In Black Hole, Armstrong drops an impossible celestial void into the centre of a sentimental Australian landscape, collapsing illusion, nostalgia, and certainty in a single gesture.

The crisp dotted perimeter — a recurring Daubist device — reads like a boundary, a warning, or a membrane between worlds. Inside it: total blackness, swallowing the landscape whole. Outside it: the untouched painterly fiction of a colonial idyll. The juxtaposition is sharp, funny, unsettling, and conceptually loaded.

The work functions as both critique and ceremony: a hole as an act of erasure, but also as a portal. A reminder that what is missing from these old pictures — stories, people, time, truth — can’t simply be painted back in. Instead, Armstrong honours that absence by making it visible.

Enquiries: drillerjet@me.com

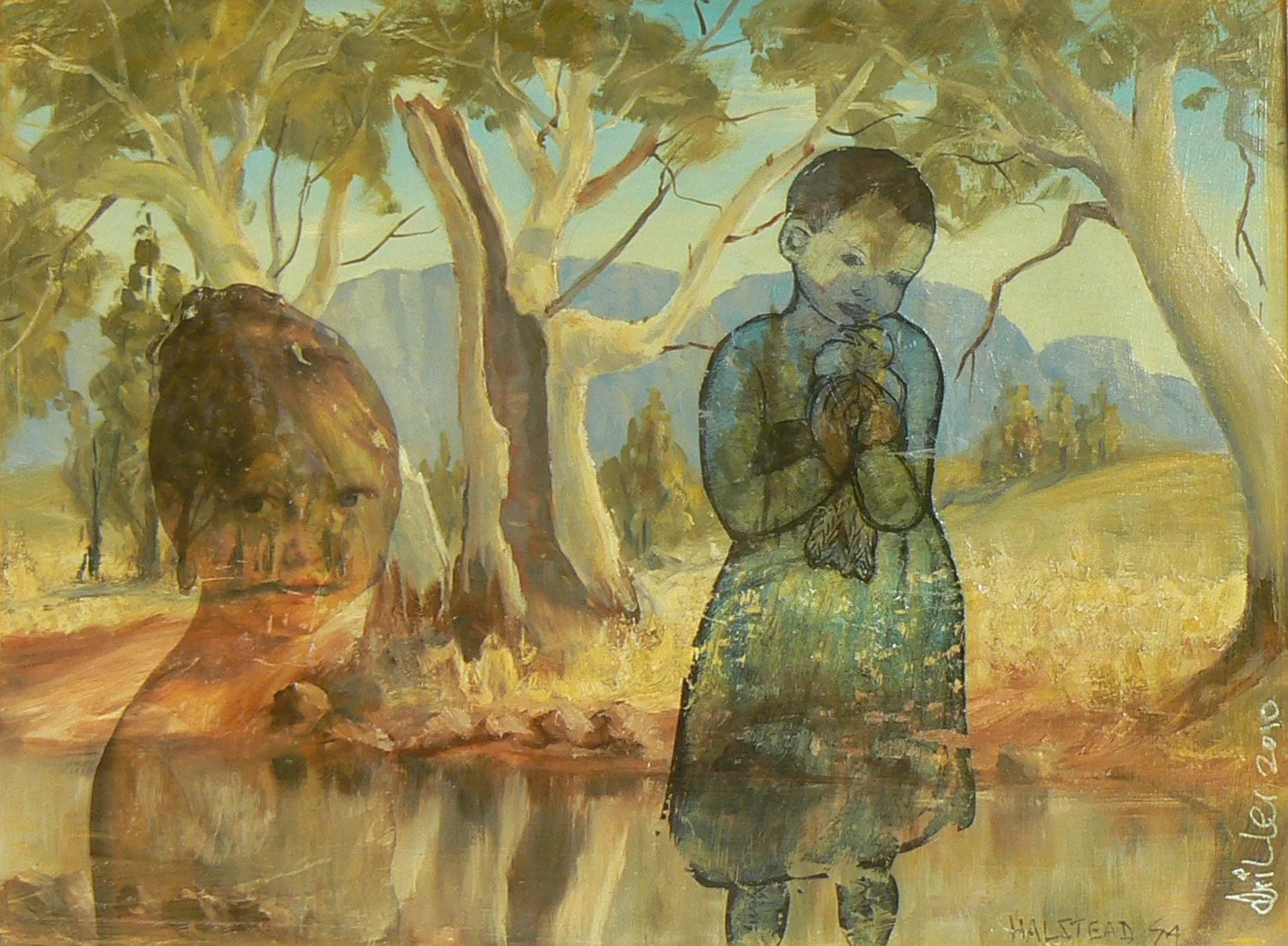

Sad Buffalo Girls (RIP Malcolm McLaren), 2010

H 71 cm × W 86 cm

Gel medium transfer (Picasso figures) on original landscape painting

$5,500

( One of the Artist’s Personal Favourites and kept in his personal collection for well over a decade and only shown once in exhibition)

Sad Buffalo Girls is one of the most haunting and poetic works in the entire Daubist canon—an early masterpiece where the visual language of appropriation, memory, and Australian pastoral mythos first fused into something entirely new.

Set against a classic Halstead landscape, two “borrowed” women—lifted from Picasso but softened through gel-transfer—appear not as intruders, but as ghosts of modernism wandering into the bush. The figures feel both out of time and deeply embedded in it, dissolving into the painting like memories that refuse to settle. Their translucent bodies and downcast gestures evoke the atmosphere of Malcolm McLaren’s Buffalo Gals, whose passing the work quietly commemorates: a cultural remix pioneer honouring another.

This daub is an elegy and a resurrection at once—where the Australian landscape becomes a stage for grief, art history, and the strange tenderness of remix culture. Few works illustrate the philosophical foundations of Daubism so clearly: to reanimate what was discarded, to let images speak across eras, and to reveal the emotional charge hidden in the collision of worlds.

Contact for purchase or enquiries:

📧 drillerjet@me.com

Portrait of the Previous Artist (2002)

(the previous artist was a communist)

H 68 cm × W 56 cm

Painted Daubist intervention over original landscape painting

$1500.00 (2025 price)

In this work, Driller Jet Armstrong transforms a modest found landscape into the imagined face of its original maker. Portrait of the Previous Artist belongs to a rare early-2000s Daubist series in which the artist reanimated anonymous or forgotten painters by reconstructing their “likenesses” directly over their own abandoned canvases. The premise was simple and wickedly clever: if these landscapes once held a worldview, why not let them now hold the artist themselves?

Here, the fictive painter—described by Driller as “a communist”—emerges as a fractured, cubist-inflected figure mapped across the surviving terrain beneath. The palette is bold, the lines assertive, the face both iconic and unstable. What results is a portrait that dislodges authorship: the previous artist is simultaneously honoured, overwritten, resurrected and replaced.

As an important early articulation of Daubism, this work captures the movement’s core provocation:

every painting already contains its predecessors, so why not bring them forward and let them speak?

Contact for purchase or enquiries:

📧 drillerjet@me.com

New Year’s Eve 2019 (2020)

H 55 cm × W 85 cm

Acrylic Daubist intervention on original painting

$2500.00

On the cusp of 2020, the world celebrated in ignorance. A virus was already moving silently across borders, bodies, and lives — and within weeks, nothing would be the same. New Year’s Eve 2019 is one of the earliest known artworks to directly engage with the COVID-19 pandemic, created before most of the world had even learned the word coronavirus.

Driller Jet Armstrong overlays an ornate classical dinner tableau with erupting red viral forms — Daubist additions that behave like the virus itself: invasive, multiplying, blind to class or privilege. The genteel 18th-century revellers lift their glasses in a moment of luxury and oblivion, unaware that something microscopic, unstoppable, and utterly indifferent is already at the table with them.

The work captures both the surreal comedy and the existential dread of the pandemic’s earliest days:

you may have it, someone you know may have it… but no one can be certain.

Armstrong’s daub here is not simply an intervention — it is contamination as art practice, the viral logic made visible.

A key historical Daubist work and a rare example of art made during the emergence of the global crisis rather than after it.

Enquiries:

📧 drillerjet@me.com

Woman with a Clear Plastic Umbrella (2025)

H 66 cm × W 56 cm

Oil on original landscape painting

$3000.00

In this luminous 2025 Daub, Armstrong channels the ghost of John Singer Sargent, slipping a figure of impossible contemporaneity into a nostalgia-soaked rural Australian landscape. Her clear plastic umbrella — a resolutely modern, mass-produced object — becomes the quiet rupture.

Painted in feathered oils that mimic Sargent’s vaporous whites and delicate atmospheric handling, the figure stands as both apparition and intruder: a woman who does not belong to the colonial pastoral fantasy behind her, yet occupies it with full authority.

The result is a temporal collision typical of Daubism:

a 19th-century dreamscape confronted by a 21st-century woman who refuses to disappear.

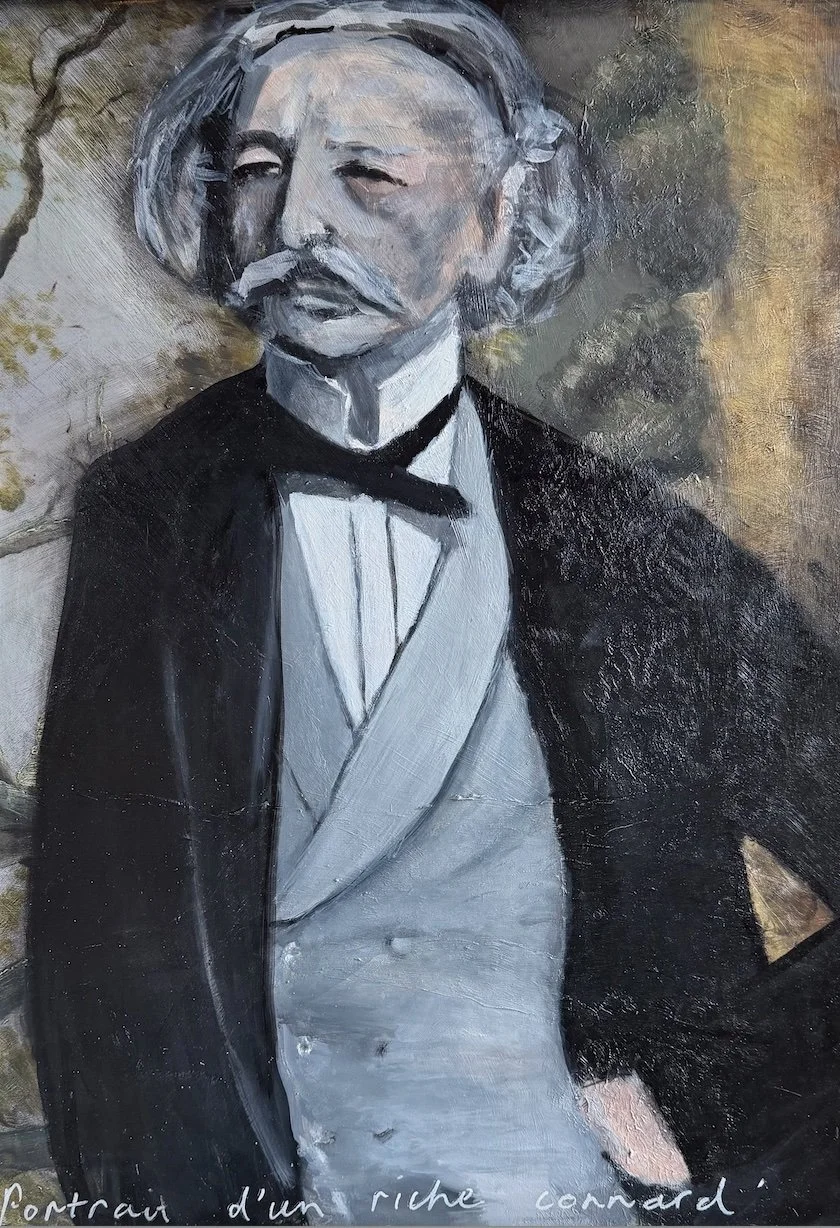

Portrait d’un riche connard (2025)

Oil addition on original landscape painting

H 80 cm × W 56 cm

$3,000.00

Portrait d’un riche connard is a study in inherited comfort — and in the quiet violence that privilege performs while appearing perfectly civilised. Painted over an anonymous Australian landscape, the work hijacks the visual language of John Singer Sargent to expose a figure who is both impossibly refined and spiritually hollow, a man upholstered by class, insulated by history, and utterly untouched by the world he claims to survey.

His face — borrowed, stolen, repurposed — floats above a country that was never his to begin with. The Daub collapses European aristocratic portraiture into the Australian pastoral myth, revealing the absurdity and arrogance embedded in both traditions. What emerges is a critique of white privilege as a landscape: something so normalised, so ambient, that many beneficiaries mistake it for natural scenery.

The title, written bluntly in French, refuses politeness. It tells the truth plainly: wealth, when paired with entitlement, becomes a kind of moral disfigurement. And yet the painting is not simply an insult — it is a mirror held up to a lineage of inherited power, asking viewers to consider who gets to stand confidently in a landscape, and who disappears beneath it.

This work sits at the sharper edge of Daubism: appropriation as scalpel, humour as weapon, portraiture as indictment.

Leaving Puzzleton 2018

mixed media on original landscape painting.

$3500.00

Leaving Puzzleton captures a moment of quiet departure from a world still unfinished. A lone figure walks away as structures dissolve into puzzle pieces—some fitted, some missing—suggesting a place held together by memory, habit, and partial understanding. The Daubist approach blurs certainty, allowing the image to exist between completion and collapse.

Voice (2023)

Gel medium transfer on original landscape painting 50 cm W 40 cm H

$1200.00

Text:

Voice takes the glossy, hyper-commercial logo of the TV show The Voice and rips it out of entertainment culture, repurposing it as a symbol of Australia’s 2023 referendum — a moment when a nation was asked a simple question but revealed a complicated soul.

The gel-medium transfer appears cracked, fractured, and incomplete, its surface splintered like the referendum result itself: a country divided, a hope interrupted, a promise deferred. The breakages aren’t decorative accidents — they become the work’s emotional architecture. Each fissure stands in for a conversation cut short, a friendship strained, a dream denied.

Against the backdrop of a quiet, harmless landscape, the appropriated logo becomes painfully loud. What was once a branding device for celebrity aspirations transforms here into a shattered emblem of civic longing — the desire for recognition, dignity, and structural change.

In true Daubist form, Voice exposes the violence of visual culture: how symbols can be re-sold, re-mixed, and re-deployed to tell new truths. Here, the pop logo no longer promises discovery; instead, it testifies to a national failure to listen.

A work about hearing, not singing.

A work about silence, not applause.

A work about the Australians who voted yes — and the heartbreak that followed.

The Batchelor and Spinsters Ball (2014)

Oil on original landscape painting

H 46 cm × W 54 cm

$2200.00

The Batchelor and Spinsters Ball recasts the Australian outback as a desolate stage for that most awkward and hopeful of rituals: the search for connection. Borrowing its spectral figures from Edvard Munch, the work dislocates his famously anxious bodies and resettles them in a paddock at dusk — a place where loneliness has been naturalised, where desire and disappointment drift like dust across the horizon.

Each figure appears both present and absent, engaged in the choreography of courtship yet emotionally suspended, as if unable to bridge the distances between them. The original landscape painting, with its burnt-orange sunset and rural homestead, becomes a theatre for human longing. Into this inherited scene, the Daubist intervention introduces the Munchian silhouettes: stiff, uncertain, yearning — but also strangely resigned.

In combining appropriated expressionist angst with a quintessentially Australian social ritual, the work transforms a familiar cultural event into something more universal and unsettling. This is the dating game as existential tableau: the outback not as frontier, but as emotional desert; the ball not as celebration, but as a gathering of people who fear they may never truly find each other.

A portrait of isolation disguised as a dance.

The 4 Dingbats of the Apocalypse (2009)

Mixed media on original landscape painting, framed behind glass

H 50 cm × W 60 cm

$3,200.00

The 4 Dingbats of the Apocalypse is Daubism at its most irreverent: a gleeful collision between a polite Australian landscape and a parade of plastic neon smiley-faced absurdities. Instead of horsemen, the apocalypse arrives here as four grinning, brightly coloured “dingbats” — supermarket-era talismans of forced happiness, cheap optimism, and mass-produced cheer.

Suspended in front of the original pastoral painting like an after-market spiritual upgrade, these plastic faces flatten the depth of the scene, interrupting the natural order with the synthetic. The tension is both comic and unsettling: a dying landscape punctured by relentless smiles, the end of days packaged as children’s stationery.

The work captures a moment when consumer culture promised joy at bargain prices while the world quietly unravelled in the background. The apocalypse here isn’t fire and brimstone — it’s distraction, denial, and the compulsory grin.

A playful, biting prophecy disguised as a joke.

Bush Kids (2020)

H 40 cm × W 48 cm

Gel medium transfer on original landscape painting (canvas)

$2,200.00

Bush Kids captures a hazy memory of childhood that never quite belonged to the settler imagination yet was endlessly projected onto it. Three figures — wild, sun-bleached, half-mythic — flicker across the surface like ghosts of another Australia, transferred imperfectly through gel medium so their bodies fracture, blur, and partially dissolve into the painted bush beneath.

The work stages two histories at once: the original landscape’s idealised pastoral fantasy, and the overlay of a stolen image whose imperfect transfer exposes every seam of cultural interruption. The children appear both embedded in and estranged from the land, as if surfacing from a dream the country once had about itself.

This is Daubism as truth-telling: memory resisting erasure, childhood as contested terrain, and the Australian landscape painting cracked open to reveal the country’s layered, uncomfortable, and unresolved past.

Landscape Dreaming with Trees and a Bridge (2023)

H 51 cm × W 61 cm

Gel medium transfer on original landscape painting

$2,200.00

In Landscape Dreaming with Trees and a Bridge, the gentle nostalgia of a traditional pastoral scene is overrun—beautifully, deliberately—by a cartography of dreamtime marks, circular currents, and abstracted pathways. The gel medium transfer creates a misted, half-remembered quality, allowing the original landscape to flicker through like a suppressed memory or a whispered origin story.

The overlaid symbols do not decorate; they reroute the entire image. As the bridge arches quietly in the background, the surface becomes a map of competing sovereignties: settler topography beneath, and a pulsing, mnemonic system above—country dreaming itself back into visibility.

This work embodies a core Daubist principle: that every landscape painting in Australia already contains another world beneath it, and that the act of daubing is a form of revelation rather than intrusion.

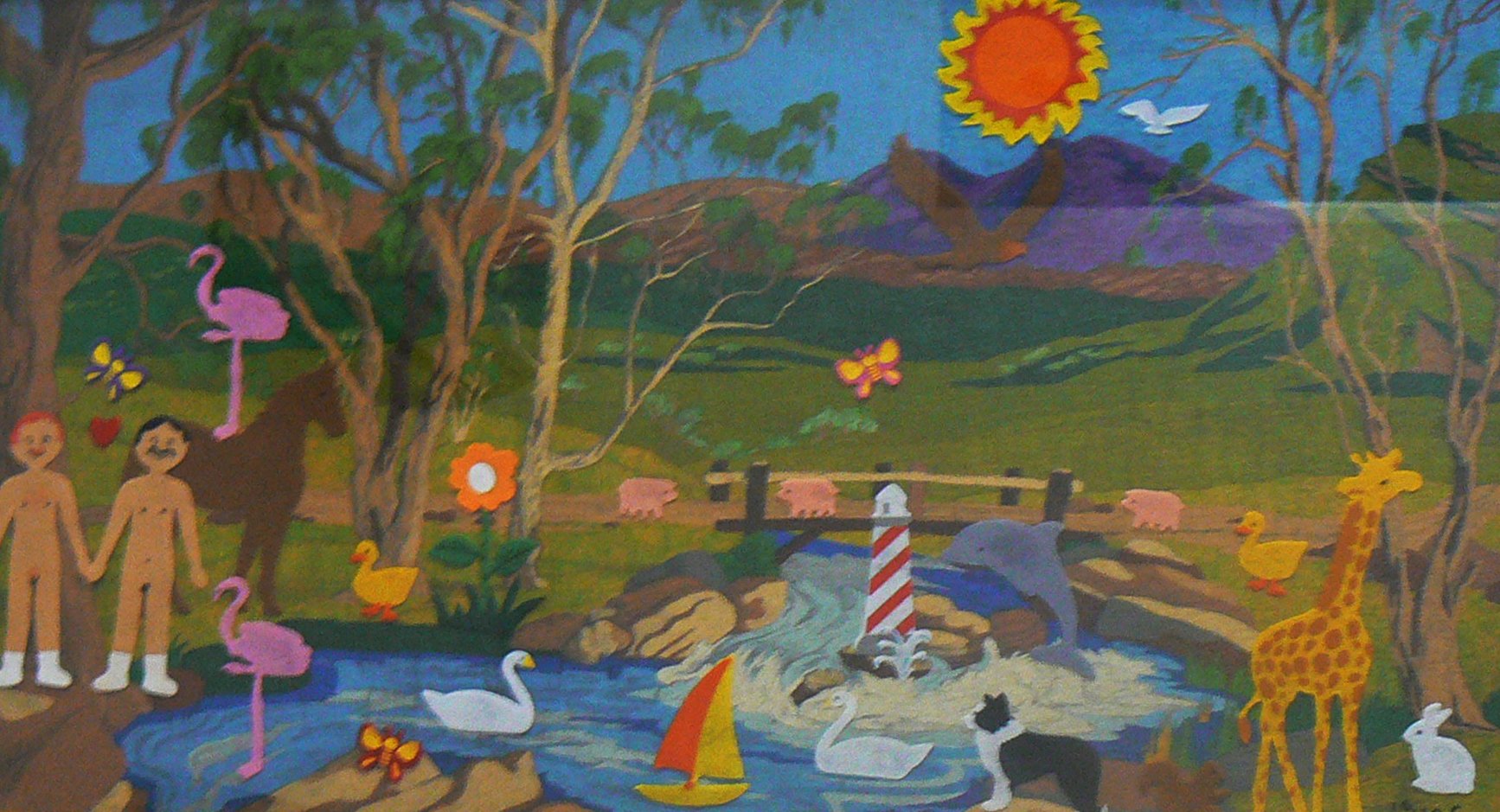

The Gay Wedding, 2009

Felt figures on original Australian landscape painting

90 × 120 cm, framed behind glass

$2500.00

The Gay Wedding is a riotous Daubist re-imagining of the Australian pastoral fantasy—an Edenic bush scene where nothing behaves as it should, and everything behaves far better than expected. Onto a once-earnest outback landscape, Armstrong introduces a mischievous parade of felt creatures, toy-like symbols, and two jubilant grooms holding hands at the edge of a creek. Their presence—so cheerfully unapologetic—reorders the landscape around them. Flamingos mingle with swans, pigs wander across a tiny bridge, a giraffe peers in from the right, and a dolphin improbably erupts from the rapids near a red-and-white lighthouse that has absolutely no business being inland.

In classic Daubist fashion, the work destabilises the solemnity of the original painting, replacing it with a playful cosmology where love is abundant, species co-exist without hierarchy, and the strict borders of “Australian landscape painting” dissolve into an open invitation. It is a celebration not only of queer joy but of Daubism’s core principle: the world becomes more alive when the artist daubs, disrupts, and reclaims the already-made.

Behind the humour lies a quietly political gesture: a utopian dreamscape offered in 2009, years before Australia’s hard-won marriage equality vote. The felt figures, with their handmade immediacy and childlike honesty, stand in contrast to the often rigid debates of the time. Here, love simply exists—warm, bright, and natural as the exaggerated sun glowing above the hills.

A tender provocation, a celebration of difference, and a gleeful rewriting of landscape traditions, The Gay Weddingremains one of Armstrong’s most beloved Daubist works: joyous, anarchic, and utterly sincere beneath its glittering absurdity.

If a Unicorn Farts in a Forest, 2020

Mixed media on original landscape painting — $2500 59 cm H 69 cm W

In this work Armstrong inserts a gleaming, cartoon-bright unicorn into an otherwise earnest Australian landscape, pushing the collision between kitsch fantasy and colonial pastoral painting to its most absurd conclusion. The rainbow—emerging not from the heavens but from the creature’s rear—functions as both a visual punchline and a conceptual rupture. It breaks the solemnity of the inherited landscape tradition and replaces it with an unapologetic act of irreverence.

Like much of Armstrong’s Daubist practice, the intervention exposes the original painting’s seriousness as a constructed illusion. The unicorn, with its candy-coloured emission, operates as a kind of anarchic truth-teller: a reminder that the myths embedded in landscape painting are no less fantastical than the creature now occupying it.

A playful desecration and a pointed critique wrapped in the same gesture, If a Unicorn Farts in a Forest continues Armstrong’s mission to liberate the landscape from its own self-importance—one rainbow at a time.

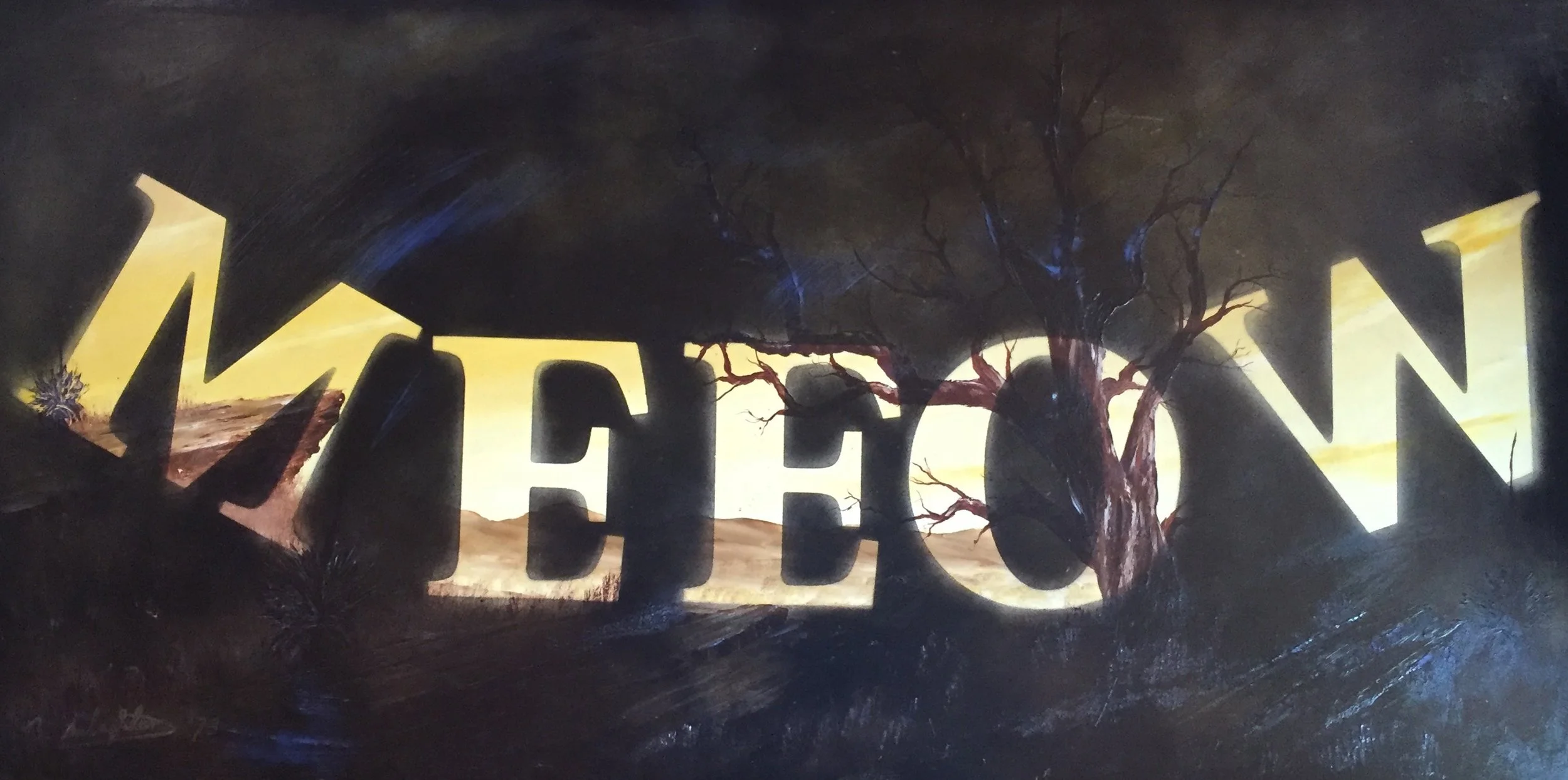

Call of the Australian Bush

2026

Mixed media on original landscape painting

1700 mm (W) × 600 mm (H)

$3,500 AUD

Call of the Australian Bush fuses language and landscape into a single psychological terrain. The word “MEEOW” is carved from light, revealing an internal world of scorched earth, distant hills and a solitary, skeletal tree—an image that oscillates between invitation and warning. The bush here is not simply scenery, but a presence: ancient, watchful, and charged with cultural memory.

In keeping with Driller Jet Armstrong’s Daubist practice, the work appropriates and intervenes upon an existing landscape, collapsing representation and inscription. Text becomes topography. The romantic tradition of the Australian bush is disrupted by a graphic intrusion that both frames and consumes it, suggesting the bush as something that calls, seduces, endures—and outlasts us.

At nearly two metres wide, the painting operates like a cinematic horizon: immersive, confrontational, and quietly uncanny. It speaks to Australia’s deep mythologies of isolation, survival, and spiritual pull, while questioning who gets to name, frame, and own the land visually.

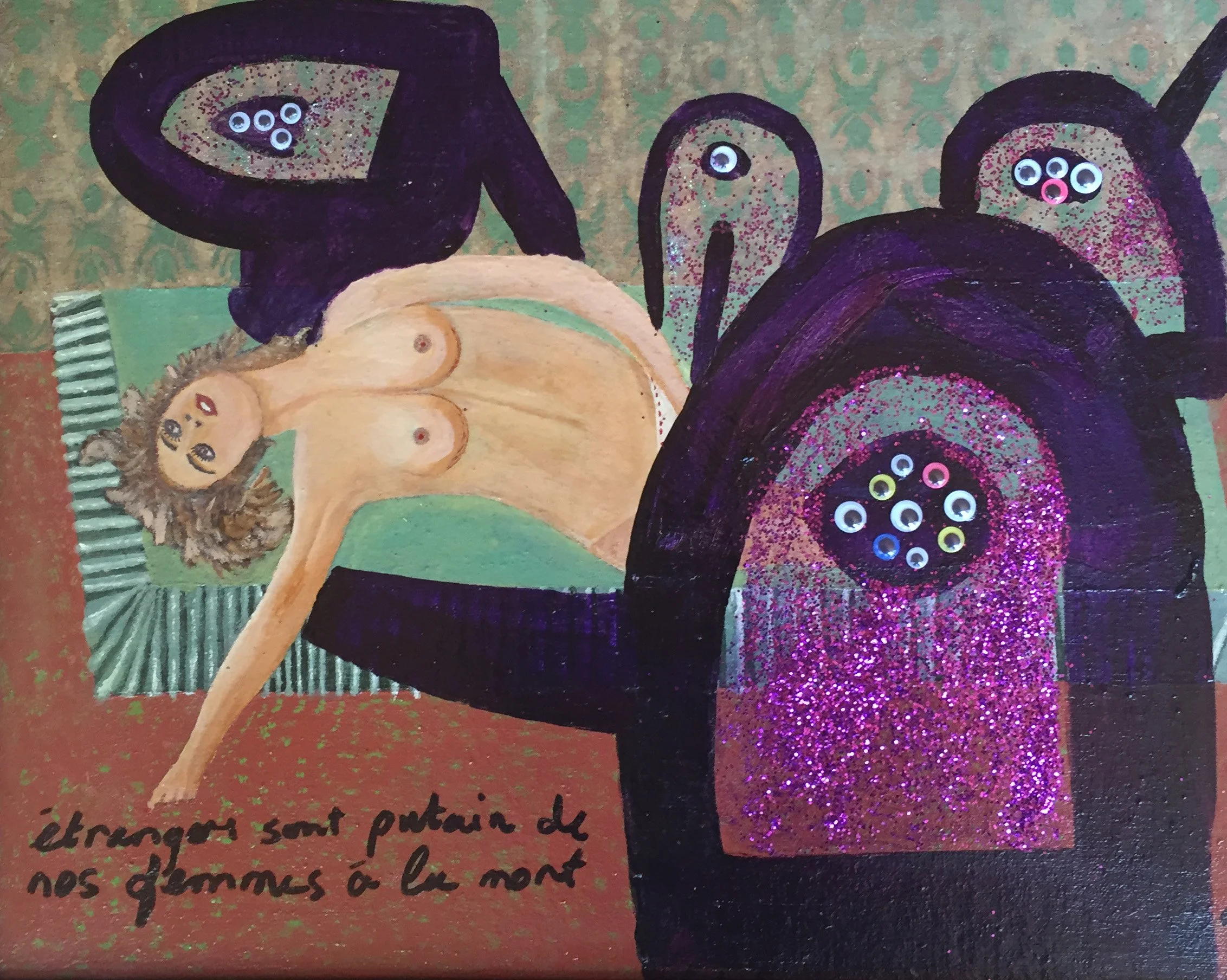

Aliens Are Raping Our Women to Death

Mixed media on original painting

(After Enrico Baj)

$3000.00

Modelled explicitly on Enrico Baj’s savage Cold-War grotesques, Aliens Are Raping Our Women to Death operates in the territory of satire, hysteria, and visual assault. Baj used monsters, generals, and mutants to expose the absurdity and cruelty of power structures; Armstrong extends that lineage into a contemporary Daubist theatre of invasion, paranoia, and violation.

The central female figure — rendered with deliberate vulnerability and art-historical awkwardness — lies suspended between dream and nightmare, surrounded by looming, amoebic alien forms studded with glittering, ocular wounds. These creatures are not science-fiction fantasies but symbolic intrusions: embodiments of fear, propaganda, and the historic use of sexual terror as a political and psychological weapon.

The lurid palette, childlike distortions, and decorative sparkle destabilise the horror, producing a grotesque dissonance that echoes Baj’s own strategy — seducing the eye while indicting the subject. Violence is not illustrated for spectacle, but staged as an accusation: against conquest narratives, misogynistic mythologies, and the long tradition of exploiting the female body as a site of cultural anxiety.

In Daubist terms, this is a work of collision. Found painting meets surreal intervention. Humour meets brutality. Beauty meets corruption. It refuses comfort, insisting instead on confrontation — a hallucinatory tableau where invasion is not extraterrestrial, but deeply human.

Hybirdus Dyslexia (2015)

Slightly transformed original painting

Mixed media on found painting

$2500.00

Hybirdus Dyslexia occupies a distinct place within the Daubist canon as a work of subtle mutation rather than overt daubing. An existing painting of a stork in a reedy creek landscape is gently but decisively transformed into a hybrid creature — its anatomy simplified, its head rendered mask-like, its presence hovering between bird, spirit figure, and invented species.

The invented Latinised title, Hybirdus Dyslexia, deliberately misnames itself. “Hybrid” becomes “Hybird.” Error is not corrected; it is preserved and elevated. Dyslexia is framed not as a deficit but as a generative condition — a productive slippage through which misreading and misnaming give rise to new forms. Language mutates alongside image.

Unlike the later, more confrontational Daubs, the intervention here is restrained. The reedy creek, watercourse, and grasses remain largely intact, grounding the work in a recognisable natural setting. Into this believable ecology enters something that resists classification. The creature does not belong to any known taxonomy. It smiles faintly. It stands improbably. It destabilises the image not through violence, but through quiet wrongness.

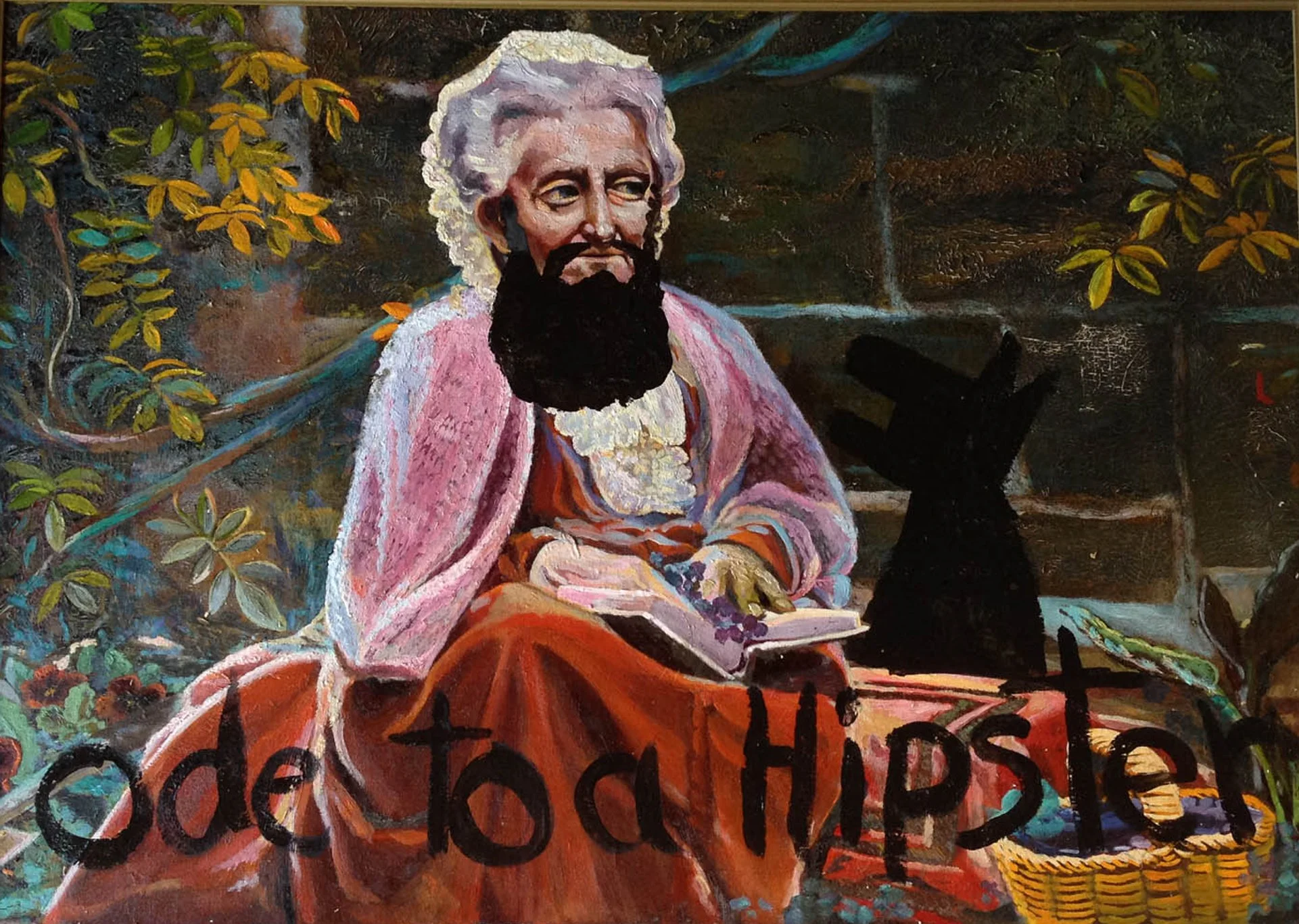

Ode to a Hipster (2019)

acrylic on original portrait painting.

$2500.00

Ode to a Hipster is a Daubist reflection on curated authenticity. A classical figure is reworked through interruption, concealment, and deliberate defacement—honouring the hipster ethic of remixing the past while refusing to revere it intact. The beard is imposed, the text is scrawled, tradition is sampled rather than preserved.

Daubism rejects polish in favour of intention. Like hipster culture, it values process over perfection, reference over originality, and irony as a form of sincerity. This work treats history as material—not authority—allowing classical imagery to be worn, altered, and contradicted.