Lineage of Daubism

Marcel Duchamp → The Conceptual Turn

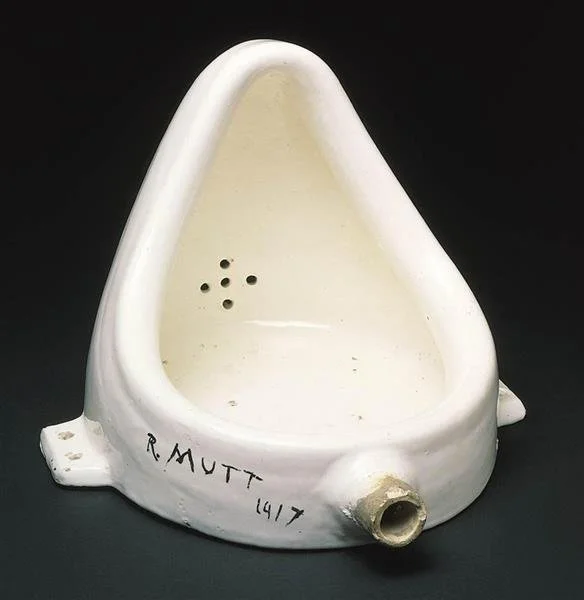

Daubism traces its earliest philosophical ancestors to Marcel Duchamp, who shattered the assumption that an artwork must be handcrafted or unique. With the readymade, Duchamp opened the possibility that the pre-existing world—objects, images and cultural debris—could be treated as legitimate artistic material. Daubism inherits this permission: the pre-existing painting becomes a site, not a limit.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917.

Sherrie Levine → Appropriation as Critique

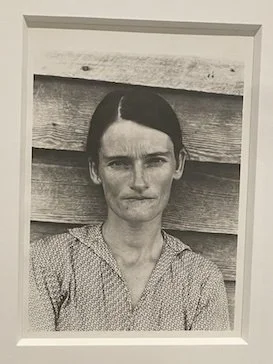

Sherrie Levine sharpened appropriation into a critical tool. By re-photographing canonical images by male artists, she exposed authorship, ownership and patriarchy as unstable concepts. Daubism absorbs this critical spirit but redirects it into paint: the daub becomes a disruptive, humorous, sometimes confrontational gesture applied to an image already loaded with cultural authority.

Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans, 1981.

Asger Jorn → Altering the Found Painting

Danish artist Asger Jorn’s Modifications form a crucial pre-Daubist precedent. Jorn painted wild, expressionist figures and marks onto anonymous landscape paintings found in flea markets, gleefully vandalising bourgeois taste. Daubism echoes this interference but shifts the emphasis: where Jorn sought anarchic revolt, Daubism pursues a layered palimpsest—Australia’s art histories, pop culture, politics, Indigenous motifs and personal mythology stacked on top of one another.

Asger Jorn le-canard-inqui-tant-1959

Sophie Calle → The Art of the Trace

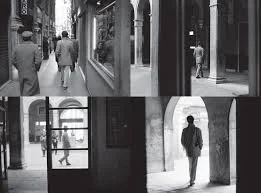

Sophie Calle’s work is built on following, documenting and infiltrating the lives and spaces of others. Her practice foregrounds ethics, intimacy and the act of looking. Daubism borrows her attention to the social story behind an image. Each daubed painting is not just an object but the residue of a chase: works rescued from auction rooms, op shops, junk shops and forgotten corners of Australian suburbia, all carrying traces of previous owners, tastes and narratives.

Sophie Calle, Suite Vénitienne (detail). 1979/1980

Enrico Baj → Political Interference

Enrico Baj’s anti-authoritarian collages and grotesque generals inject satire, absurdity and protest into traditional forms. Daubism likewise interrupts the polite Australian landscape tradition—those safe, misty gums and golden paddocks—with humour, critique and mischief. The daub acts as aesthetic interference, confronting national myths, nostalgia and the comforts of the picturesque.

Des êtres d'autres planètes violaient nos femmes, 1959

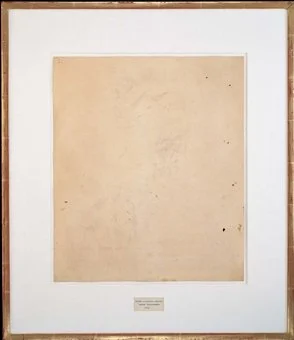

Robert Rauschenberg → Erasure and Renewal

With Erased de Kooning Drawing, Robert Rauschenberg proposed that removal itself could constitute an artwork. Erasure became a form of mark-making. Daubism extends this logic through addition rather than deletion: the existing painting is not destroyed but transformed, its original image both honoured and overwritten. Each daub produces a new work born from a previous work’s partial collapse.

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953.

Driller Jet Armstrong → The Founding Gesture (1991–Now)

Daubism crystallises in early 1990s Australia when Driller Jet Armstrong applies a decisive daub onto an existing landscape painting, inaugurating a practice that has unfolded over decades. From Charles Bannon to Charles Fridrych and beyond, Armstrong systematically re-enters the Australian landscape tradition with lightning bolts of paint, rock-art figures, unicorns, text, DIY heraldry and pop-cultural fragments.

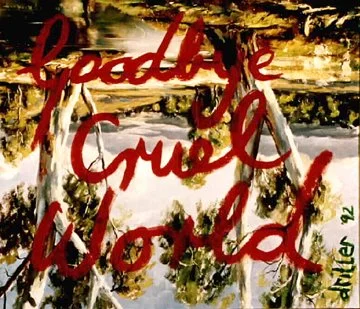

Suicide Note on Charles Fridrych Landscape (1992) becomes an early, emblematic work in this lineage: a found painting is not merely “updated” but overwritten with a new psychological script. The serene landscape becomes the stage for a handwritten crisis, collapsing postcard sentimentality into something darker, funnier and more contemporary. The key Daubist rule is in force here and remains non-negotiable:

A Daub must occur on an original painting—never on a print or reproduction.

Over time, Armstrong’s Daubism weaves together Indigenous visual references (sought with increasing ethical care), Australian kitsch, personal mythologies, DJ culture, media noise and art-historical quotation. The daub is not a single gesture but a cumulative method: an ongoing argument with what Australian painting has been, and what it might still become.

Driller Jet Armstrong - Suicide note on Charles Frydrych landscape 1992