DAUBISM - An Australian art movement founded by Driller Jet Armstrong (1991–present)

Correspondence with Professor Anne Poelina (2020)

In May 2020, Driller Jet Armstrong received a remarkable and deeply considered response from Professor Anne Poelina, a Nyikina Warrwa woman of the Kimberley region—an internationally respected academic, filmmaker, community leader, and advocate for human and earth rights. Poelina, whose groundbreaking doctoral work explores First Law, multispecies justice, and the interdependence of land, waters and people, wrote to Armstrong directly regarding the ethical and political dimensions of his Daubist practice.

In her email of 21 May 2020, Poelina addressed the complexities of cultural respect, appropriation, and artistic intervention with a clarity that few public figures have been willing to articulate:

“Driller, I agree with your stand as giving voice to the voiceless and your work does not consume the Indigenous/Aboriginal Art but makes its own deconstruction in your own way to give meaning to the need for decolonising our minds towards justice and freedom.

We are trying to wake up the consciousness of the people and your work does that… remember also the diversity of Indigenous/Aboriginal people… but the process must always be to honour the land and its people and the way they are storying, be it through many different mediums.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing… but if you are unable to contact the artist how do you bring them on this journey of reconstruction?

This is a big topic for our nation who live with the illusion we are in a democracy when we are still dictated to by a constitutional monarchy… the Queen is still in charge and we need to redefine who we are in modernity as Australians.

Have you seen the artwork of John Reid Untitled (Collage of Australian banknotes)? … it’s a similar story but he is cutting up real dollars to make his artwork visible… he has really been through a similar journey!

It’s an interesting deconstruction on how we value art as the champion for democracy and justice.”

— Professor Anne Poelina, 21 May 2020

Poelina’s words capture something essential about Armstrong’s project:

that Daubism is not an act of cultural consumption, but a deconstruction, a calling-to-consciousness, and a deliberate engagement with the politics of image-making in Australia.

Her response stands as one of the most significant external validations of Armstrong’s decades-long exploration into the ethics of intervention, the responsibilities of artists working within contested histories, and the urgent task of reimagining Australian identity in a post-colonial present.

Crop Circle on Bannon Landscape 2 (2001)

Spray-painted stencil on original landscape painting by Charles Bannon

Created on the 10-year anniversary of the original 1991 provocation, this work revisits—and doubles down on—the gesture that ignited Daubism. The crisp crop-circle stencil slices through Bannon’s lyrical landscape like a coded transmission, refusing nostalgia and demanding a reckoning.

Part homage, part disruption, part time-loop, it marks the moment Daubism became not just an act of vandalism or humour, but a philosophy: the right to intervene, overwrite and re-speak the Australian landscape.

Daubism began in 1991 with a single, explosive act: a white crop-circle symbol sprayed onto an inherited Charles Bannon landscape. What followed was not a fad, a phase, or a prank — but a full art movement that continues more than three decades later, challenging ideas about ownership, authorship, territory, visibility and memory in Australian painting.

Daubism takes existing artworks — usually forgotten, discarded or devalued second-hand landscape paintings — and adds to them, rather than painting over them. A Daub is an intervention, not a deletion. The original artwork must remain visible. Its history must stay intact. And the new mark must sit with the painting, not replace it.

This simple premise leads to profound consequences:

Who owns an image once another artist intervenes?

Why were First Nations people removed from colonial landscapes in the first place?

What happens when “high art” and “pop culture” collide on the same canvas?

Can you expose the politics inside an image simply by adding to it?

Daubism answers yes to all of these questions.

It is an art movement built on visibility, disruption, humour, collision, and cultural honesty.

Core Principles of Daubism

1. The original painting must remain.

Daubism never erases. It reveals.

2. A Daub is an intervention.

The act itself — the addition — is the meaning.

3. Two worlds must meet on the same surface.

Western pastoral painting + First Nations visual presence → shared Country.

4. All images have history.

Daubism exposes the power, absence and ideology hidden inside inherited artworks.

5. Remix is not theft — it is evolution.

Just as DJs sample sound, Daubism samples imagery.

Appropriation becomes transformation.

What Daubism Does

Daubism disrupts colonial mythologies.

It reactivates “dead” landscapes.

It pushes pop icons, rock-art silhouettes, Wandjina motifs, Basquiat heads, unicorns, jigsaw shapes, Degas ballerinas, and Picasso bathers into the polite world of Australian pastoral painting.

The result is an Australian image that is finally layered, honest, mischievous and alive.

Cultural Position

Daubism sits at the junction of:

postmodern appropriation

First Nations absence / presence

remix culture

DJ sampling

pop surrealism

Australian postcolonial critique

It is contemporary art made on top of historic art — a palimpsest, a remix, a reclamation.

Historical Significance

1991 — Crop Circle on Bannon Landscape ignites national moral-rights debate

1990s–2000s — Daubism gains notoriety through annual exhibitions & controversies

2010s — Add-Original series brings First Nations silhouettes & dotting into inherited landscapes

2020s — Renewed relevance in the age of AI image theft, appropriation debates and cultural visibility

Present — Daubism stands as a uniquely Australian art movement with international resonances

Why Daubism Matters

Because images remember.

Because nations forget.

Because art history needs interruptions.

Because Australia is not a blank canvas.

Daubism insists that every painting — old or new — carries the stories of those included and those erased.

A Daub is not graffiti.

It is reconciliation on the picture plane.

“Driller is the most mischievous artist of our time.”

— Samela Harris

Add-Original

A Daubist Expansion (2017– )

Add-Original is the evolutionary branch of Daubism—an extension of the core principle that the Australian landscape painting is not a sacred relic, but an active site of negotiation, revision, and truth-telling.

Where early Daubism used gestures of disruption—crop circles, overpainting, cultural collisions—Add-Original moves toward restoration through insertion. It is a practice of putting back what history removed.

For more than a century, Western European landscape painting operated as a silent propaganda machine: depicting a continent empty of its custodians while presenting itself as neutral scenery. Add-Original intervenes in this colonial absence by reintroducing First Nations presence, motifs, memory, and visual sovereignty back into appropriated landscapes.

This is not mimicry. It is not replication. It is a conceptual act:

a deliberate correction of the record.

Principles of Add-Original

• Reinsertion of erased subjects — silhouettes, figures, symbols and presences that recall the cultural, human and spiritual realities left outside the colonial frame.

• Respectful collision — Western landscape traditions meeting First Nations aesthetics, storytelling marks, and cosmological geometry, without claiming authorship of those traditions.

• Transparency of appropriation — unlike historical painters who hid their borrowings, Add-Original foregrounds its sampling, its sources, and its politics.

• Shared visual sovereignty — two modes of seeing occupying the same painted space, refusing the myth of an empty land.

Why Add-Original Matters

Add-Original is not an attempt to speak for Aboriginal culture but to refuse the colonial silencing embedded within the inherited image-world of Australia. It makes visible the violence of omission, and in doing so, insists on a plural, contested, and honest landscape.

Add-Original Within Daubism

If Daubism broke the frame and challenged ownership, Add-Original asks what happens after the break—when the artist becomes responsible for what they choose to put back in.

It marks a shift from pure provocation to cultural repair, from mischief to philosophy, without losing the irreverence at the heart of Daubism. Both movements share one belief:

The Australian landscape painting is not finished.

It is still being argued with.

And it still needs to be told the truth.

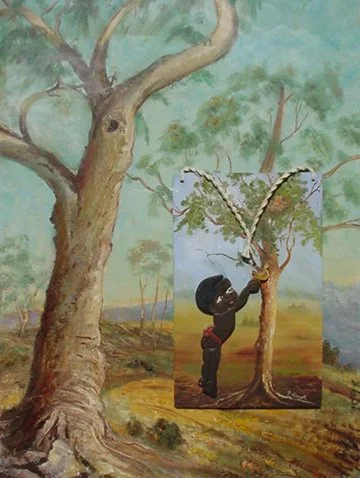

SORRY (2002)

two found paintings combined

“SORRY” is an Add-Original work in which two entirely separate paintings by unknown, non-First Nations artists are brought together to form a single, unsettling image. By sheer coincidence — or perhaps fate — the horizon lines and central tree align almost perfectly, allowing Driller to fuse the canvases into one continuous landscape. The seam is invisible, yet the disruption is profound.

Within this newly-constructed space, a stylised Black child appears to be gathering bark from the tree — a gesture borrowed from one painting and inserted into the other without alteration. Driller adds nothing; he simply combines what was already present. This act of joining exposes the ways in which Australian landscape painting has historically erased, sentimentalised, or misrepresented First Nations people.

The title, SORRY, reframes the now-one image as a quiet but pointed commentary AND predates Australia’s landmark 2008 National Apology. With no added marks of his own, Driller lets the collision of two colonial-era visions speak for itself: a single, flawless horizon binding together a fractured national narrative.

Disillusioned, Dis-Spirited and Dangerous (2017)

Paint on original landscape painting

Disillusioned, Dis-Spirited and Dangerous is one of the clearest examples of Daubism’s capacity to transform a found landscape into a charged psychological tableau. Three stylised spirit figures — each rendered in Driller’s signature Wandjina-influenced outline — stand against a stark black field that has swallowed almost all of the original painting. Only their bodies remain open, revealing glimpses of the inherited landscape beneath: fragments of buildings, bushland, and muted earth tones that survive inside their silhouettes like memories trapped within a shell.

The trio appear connected yet emotionally estranged — one watchful, one withdrawn, one blank-eyed and unblinking. Together they embody the work’s title: figures stripped of certainty, estranged from their environment, and rendered dangerous by the volatile mix of erasure, survival, and unresolved history.

By leaving the original painting visible only within the interior of the bodies, Armstrong reverses the conventional order of landscape painting: Country becomes something carried, not something standing behind. The black field becomes a void — colonial amnesia, cultural dislocation, or the internal collapse of meaning — against which these hybrid presences must negotiate their existence.

The result is a haunting, confrontational image in which old and new worlds collide within the human form itself. Here, Daubism becomes a diagnostic tool: revealing what has been lost, what remains, and what refuses to stay silent.

Lost Title (2015)

“Lost Title” stages three towering Wandjina-like spirits—figures unmistakably indebted to First Nations iconography—inside a distinctly Western landscape painting that was never meant to hold them. Each form is rendered with bold, simplified colour blocks, their white chests and radiating head-spikes holding the visual authority of ancient presences. Behind them, the inherited pastoral landscape rolls on quietly, oblivious to the interruption.

The title—or lack of one—functions as a provocation. By refusing a definitive label, the work mirrors the deeper cultural erasures that haunt Australian art history: missing attributions, suppressed narratives, overwritten sovereignties. The Wandjina figures appear not as decorative additions but as returns—assertions of a presence that long predates the colonial gaze of the original painting.

In this Add-Original intervention, Armstrong doesn’t blend traditions; he collides them. The result is an unsettling hybrid image that exposes the fractures in Australia’s visual inheritance and suggests that what is “lost” in title may be far more present in spirit.

Black Snake (2018)

Acrylic on original landscape painting

Black Snake takes an intact, anonymous colonial landscape—complete with tidy cottage, gum trees, and the familiar rhetoric of pastoral serenity—and slices a vast, sinuous void through its centre.

The matte black form is unmistakably serpent-like, edged with a constellation of white dots that both decorate and delineate the creature’s path.

In Daubist terms, the work performs two simultaneous acts:

Erasure — The snake devours most of the picture plane, eclipsing the settler-pastoral idyll and refusing its dominance.

Revelation — What remains visible through the serpent’s “openings” reads like windows, reminding us that these landscapes were never empty; what is absent speaks louder than what is left behind.

The snake—a potent figure across many First Nations cosmologies—becomes a counter-author, asserting a presence that colonial imagery traditionally overwrote. Here, it is not merely inserted but empowered: larger than the frame, larger than the narrative, larger than the polite fiction of the landscape genre itself.

Black Snake is both interruption and restoration. A reminder that beneath every “untouched” landscape lies a story, and that the act of daubing can return agency to the ground on which the image stands.

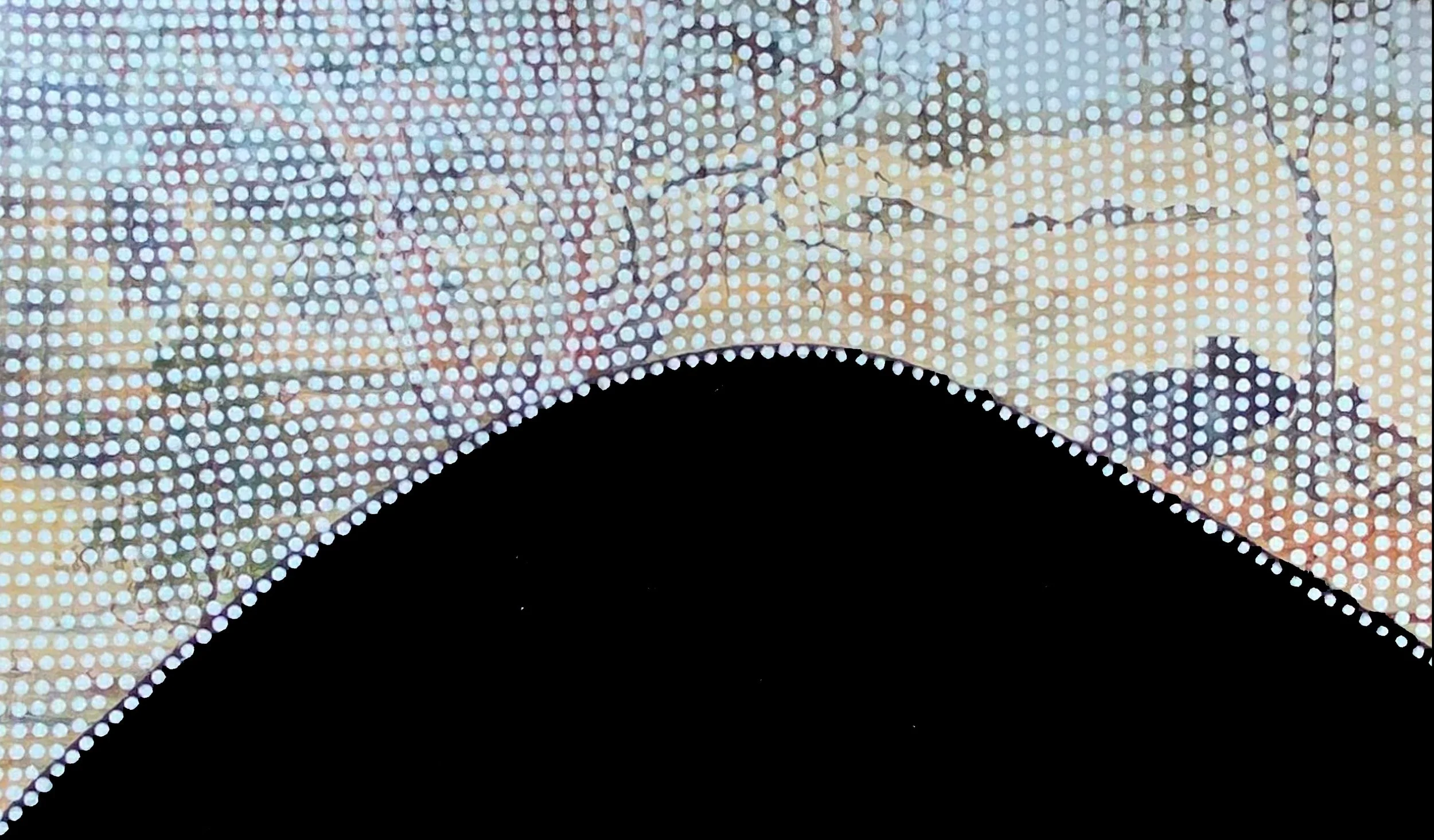

CONVERGENCE (2022)

Acrylic and dot-work intervention on original landscape painting

Convergence distills a core Daubist principle: two visual languages meeting on the same horizon. A vintage pastoral landscape—soft, tonal, and rooted in the conventions of Western painting—is partly eclipsed by a sweeping arc of deep black, its edge marked with meticulous white dotting.

The work becomes a threshold. Above: the inherited image of settler Australia. Below: an assertive field of black that refuses to behave as negative space. The dotted boundary becomes both membrane and meeting point, echoing First Nations mark-making while never claiming or reproducing it.

The result is a powerful moment of tension and balance—where one world recedes, another emerges, and the viewer is held on the line between them. In Convergence, Driller Jet Armstrong articulates the essence of Daubism: disruption as respect, interruption as dialogue, and the belief that a painting can become more honest once its layers are allowed to collide.

Breaker (2017)

Spray paint, acrylic and daub on original landscape painting

Breaker (2017) slams together two visual languages that, at first glance, should never meet: Keith Haring’s iconic breakdancer and a stylised Wandjina figure — all laid boldly over the top of a saccharine colonial landscape painting.

The figure’s pose, borrowed from Haring, becomes something entirely different once mapped onto Country. The body is filled not with flat colour but with the inherited brushwork of the original landscape, as if the land itself is erupting into movement. The black outline reads as both graffiti tag and ancestral marking; the daub is both playful and confrontational.

This is Daubism at full voltage — remixing, reclaiming, unsettling and re-authoring at the same time. Breaker turns the landscape into a dance floor, allowing First Nations presence, pop iconography, and postmodern appropriation to collide in one kinetic, irreverent image.

AN AUSTRALIAN ON THE GRAND TOUR (2021)

Painted Wandjina figure on an original European landscape painting by A. Segall.

A lone Wandjina strides through a sun-washed European port, its bold, black form disrupting the genteel calm of the Grand Tour tradition. By inserting a distinctly Australian ancestral presence into a classic continental scene, Armstrong flips the script: instead of Australians travelling to Europe to legitimise their culture, the culture travels back—assertive, uninvited, and unmistakably itself.

This work collapses geography and history into a single frame. The inherited European painting becomes a stage on which an Indigenous-coded figure refuses to play a passive role, confronting old-world romanticism with a distinctly postcolonial jolt. It is both humorous and quietly radical: the tourist becomes the intruder, and the “civilising gaze” is returned with interest.

Space Invader (2019)

Add-Original painting on found landscape

Space Invader is one of the clearest articulations of Daubism’s central tension: the collision of imported visual languages with the deep time of Country. Painted over a sentimental European-style landscape, the white figure appears simultaneously ancient and extraterrestrial — part Wandjina, part arcade-era alien, part warning flare in the wilderness.

The radiating spiral on the left acts as both target and portal, a mark that destabilises the colonial illusion of untouched terrain. The figure’s raised hand — equal parts greeting and halt-signal — confronts the viewer with the same question that underpins the entire Add-Original philosophy: Who truly belongs in this picture? And who is the intruder?

Rather than erase the original painting, Armstrong allows it to remain visible beneath the intervention, integrating the old and the new into a single unresolved field. The result is a playful but pointed work in which innocence, occupation, mythology, sci-fi and sovereignty all converge — a “first contact” scenario staged directly on the surface of the Australian landscape.

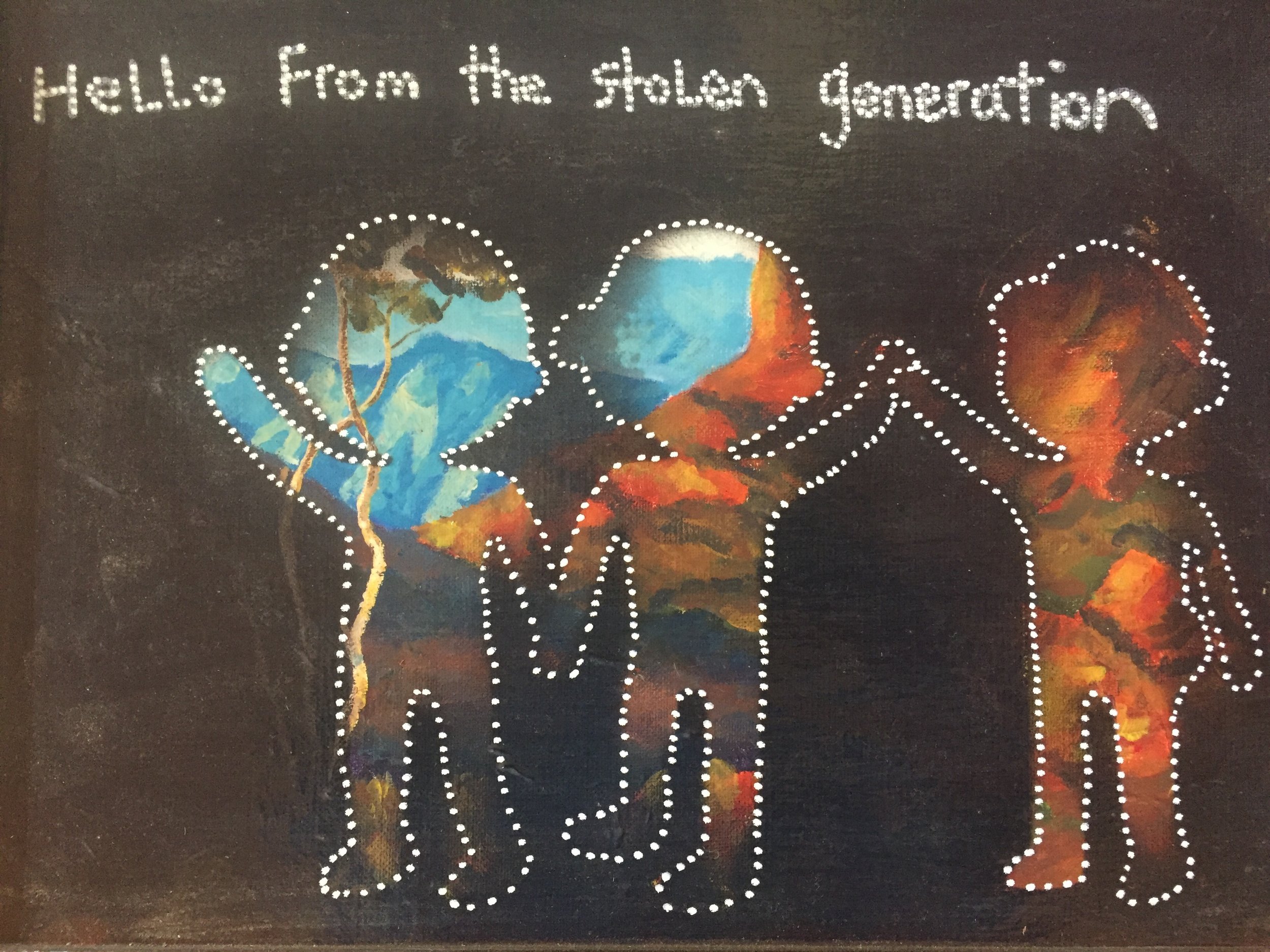

HELLO FROM THE STOLEN GENERATION (2017)

additions to original landscape painting

In this work, Armstrong cuts three child-like silhouettes from a colonial landscape, allowing the scenery behind them to fill their bodies like ghosts of Country. Each figure is edged with delicate white dotting — a visual echo of First Nations mark-making — and together they form a small procession waving toward the viewer beneath the hand-painted message, “Hello from the stolen generation.”

The piece refuses to narrate trauma directly; instead, it creates a quiet, devastating absence. The original painting’s pastoral calm is punctured by the missing children it never depicted — the landscapes they were taken from, the families they were taken to, and the history Australia is still trying to reconcile.

Armstrong’s daub transforms a polite, inherited image into a confrontational acknowledgement: the land remembers its children, even when the nation tried to erase them.

Spirits at the Waterhole (2023)

Hand-painted figures over an anonymous colonial landscape painting

In Spirits at the Waterhole, Armstrong overlays a quiet colonial bush scene with a gathering of translucent, ochre-yellow spirit figures, each rendered with the loose immediacy of children’s drawings but weighted with deep cultural resonance.

Their placement is deliberate: drifting along the bank, climbing trees, pausing at the water’s edge, the spirits reclaim the site as a place of gathering, ceremony and memory. What was once painted as an empty, uninhabited pastoral idyll is re-populated with presences—gentle, playful, and unmistakably First Nations.

By interrupting the inherited landscape image, Armstrong reveals the fiction at the heart of settler painting: the myth of emptiness. The spirits return what the original artwork tried to erase, suggesting a layered, living history beneath the colonial brushwork.

The work sits firmly within Daubism’s Add-Original mode—where the artist does not destroy the inherited painting, but activates it, opens it, and allows the past that was painted over to speak again.

The result is tender and unsettling: a landscape no longer still, but watched, shared and remembered.