SPOT PAINTING 9 (2022)

An Add-Original work overlaying Western European landscape painting with First Nations presence

Spot Painting 9 marks a pivotal moment in Daubism: the decision to deliberately merge two visual systems—Western landscape tradition and First Nations mark-making—onto a single shared Country.

Across the surface of an inherited European landscape painting, a field of hand-applied white dots spreads in rhythmic constellations. The patterning does not illustrate the scene beneath it; instead, it asserts a parallel reading of place, one grounded in First Nations visual knowledge. The dots hover between presence and disruption—sometimes softening the scene, sometimes puncturing it, always shifting the viewer’s relationship to the “original.”

The underlying landscape is not erased but recalibrated. Trees, sky, water and horizon remain visible through the daubed field, visually negotiating for space. The work becomes a site of encounter: two traditions occupying the same surface without collapsing into one another.

In Spot Painting 9, Daubism moves beyond appropriation into cultural re-alignment. The Western pastoral view is no longer the uncontested centre; the dotting overlays return the painting to Country, insisting that any notion of landscape in Australia is already layered, already contested, already shared.

It is a work of quiet insistence—simple in gesture, radical in implication.

GHOSTSCAPE (2017)

Gel transfer on original landscape painting

Ghostscape is a major early Daubist work in which Driller Jet Armstrong brings the unseen back into the centre of the Australian landscape. Using gel-transfer techniques, Armstrong overlays an inherited Western European pastoral scene with the spectral silhouettes of First Nations people — figures who were present long before the picture plane imagined by colonial art.

By layering these translucent presences onto the surface of the original painting, the work exposes the absences embedded in the settler gaze and insists on a shared, contested Country. The image flickers between what was recorded and what was erased; between the landscape as painted, and the landscape as lived.

Ghostscape stands as a key articulation of Daubism’s central proposition: that alteration is revelation — that by intervening directly into the surface of existing paintings, hidden histories, suppressed narratives, and cultural collisions are not only acknowledged but made vividly, hauntingly visible.

BREAKER (2015)

A Daubist work combining stylised Wandjina, Keith Haring iconography, and an original landscape painting

Breaker is a pivotal Daubist collision — a charged, playful, and unsettling fusion of global pop iconography, First Nations cosmology, and inherited Australian landscape painting.

A breakdancer borrowed from Keith Haring’s visual language is re-imagined as a Wandjina figure, a powerful ancestral being from the Kimberley. Within the outline of the figure, fragments of an original colonial landscape painting remain visible, preserved as the internal “body” of the form. The result is a tense, vibrating mash-up: Country, culture, and Western art history are literally embedded inside the silhouette of movement, presence, and resistance.

CALMING FORCE (2013)

A stylised Wandjina figure integrated into an original landscape painting

Calming Force is an early but fully realised articulation of Daubism’s core principle: placing two visual traditions—one inherited, one asserted—onto the same surface so neither can remain neutral.

Across the gentle haze of an original European-style landscape painting, a reclining Wandjina figure stretches across the foreground. Its form is outlined in thick, declarative lines, a graphic presence that refuses to disappear into the pastoral quiet behind it. Inside the body of the figure, fragments of the original landscape remain visible, absorbed and transformed into the Wandjina’s interior world.

The pose is relaxed, almost playful, yet the work pulses with tension. The Wandjina—an ancestral being of immense cultural authority in First Nations cosmology—interrupts the colonial idyll, not as ornament, but as a sovereign presence. Its quietness is its strength: it lies across the painting like a grounding weight, a reminder of Country’s original custodianship, asserting itself calmly, confidently, without spectacle.

Calming Force is Daubism in its distilled form: cultural overlay as intervention, humour as strategy, and coexistence as a creative and political act.

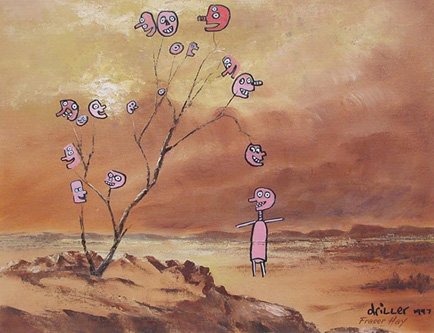

BASQUIAT DAUB (2002)

Jean-Michel Basquiat sample added to an original landscape painting

One of the early, foundational gestures of Daubism, Basquiat Daub (2002) takes a quiet, desolate Australian landscape and electrifies it with a burst of borrowed visual life. Onto a barren tree—lifeless, skeletal, almost forgotten—Driller grafts a constellation of Basquiat-inspired heads, cartoonish and impulsive, hanging like strange pink fruit.

The original landscape, painted in the subdued tones of colonial pastoral tradition, becomes the stage for a joyful disruption. The Basquiat figures animate the tree, pulling it back from stillness, teasing it into vitality. Their manic expressions, vibrating outlines, and deliberately crude energy contrast sharply with the landscape’s muted seriousness, creating a friction that is both humorous and quietly subversive.

By sampling Basquiat—a figure synonymous with New York street expression and anti-establishment urgency—Driller overlays an alternative artistic lineage onto the inherited Australian scene. The tree, once emblematic of emptiness, becomes a site of renewal, possibility, and cultural remixing.

Basquiat Daub is a playful but pivotal early articulation of Daubism: the insistence that the past is not fixed, that paintings can be re-awakened, and that new voices—borrowed, honoured, misbehaving—can grow from old branches.

CROP CIRCLE ON BANNON LANDSCAPE (1991)

Spray-painted crop-circle symbol applied to an original Charles Bannon landscape painting

The inaugural act of Daubism — the spark that ignited an entire movement — Crop Circle on Bannon Landscape (1991)marks Driller Jet Armstrong’s first deliberate “daub” on an existing artwork. In a moment that fused irreverence, critique, and play, Driller sprayed a stark white crop-circle symbol onto a traditional Charles Bannon landscape painting, an Australian pastoral scene rooted in settler-colonial visual convention.

The intervention was immediate, bold, and transgressive. The crop-circle emblem — an alien, inexplicable mark — lands abruptly on the landscape, defacing it, reclaiming it, and re-reading it all at once. By imposing a global pop-mysticism symbol onto a genteel, inherited painting, Driller destabilised the authority of the original and exposed the fragility of the “untouchable” Australian landscape tradition.

This work triggered a national controversy and a legal and moral-rights debate that would later define the Daubist project:

Who owns an image?

Whose marks are allowed on the landscape?

And what happens when an artist dares to intervene in an already-finished artwork?

Crop Circle on Bannon Landscape is now recognised as a foundational moment in Australian art history — the beginning of Driller’s long-running, mischievous, and culturally incisive campaign to remix, rework, and re-energise the inherited images of Australia.

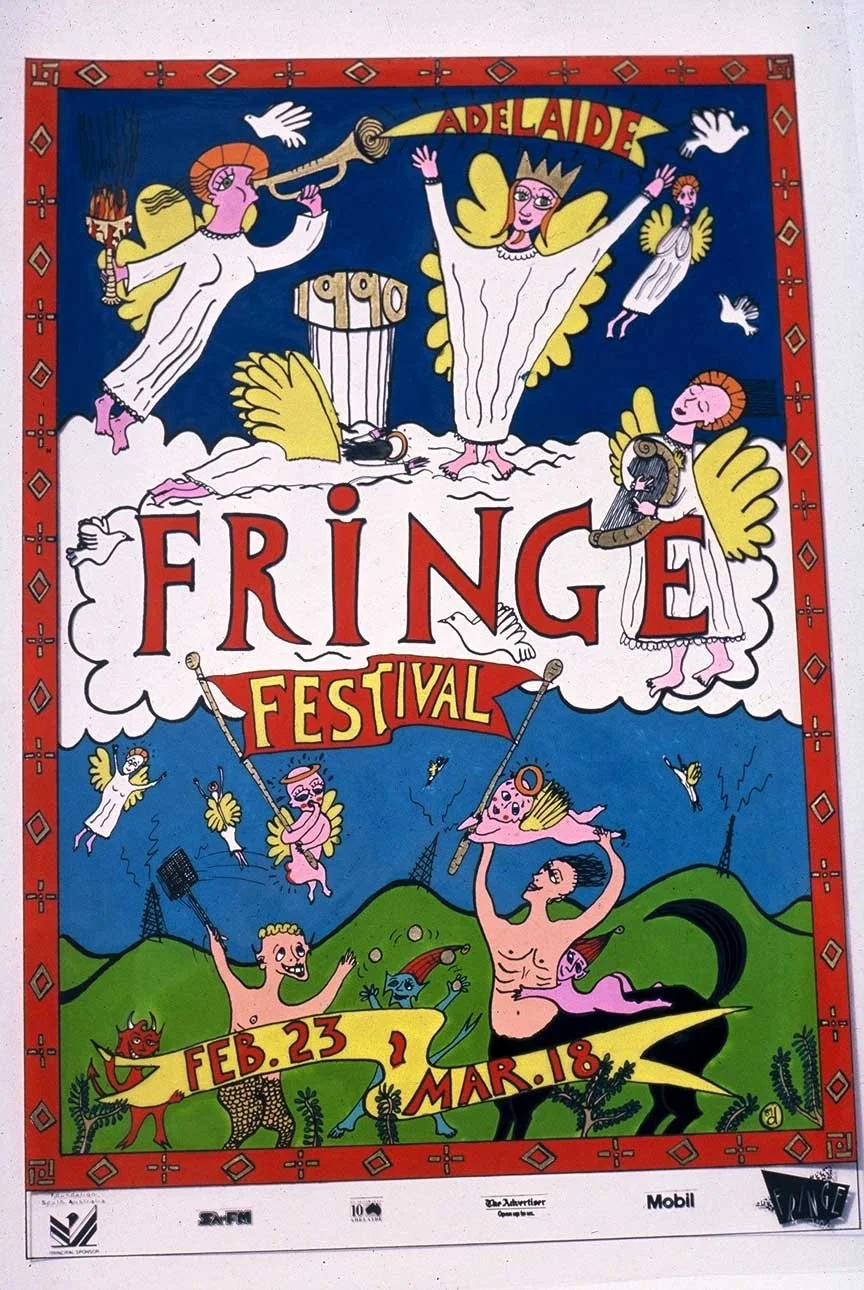

1990 ADELAIDE FRINGE FESTIVAL POSTER

(Winner — Official Festival Poster Competition)

Created in 1989 for the 1990 Adelaide Fringe, this exuberant poster marks one of Driller Jet Armstrong’s earliest major public commissions. Bursting with anarchic humour, mythic creatures and winged figures in chaotic celebration, the work captures the irreverent spirit that would later fuel the Daubist movement.

Armstrong’s characteristic visual language is already fully present: bold outlines, hyper-expressive characters, and a carnivalesque energy that upends the polite traditions of festival branding. The result is a poster that didn’t just advertise the Fringe — it became Fringe.

Winning the official competition cemented Armstrong’s reputation as a mischievous cultural agitator and positioned him as a key visual voice in Adelaide’s alternative arts scene at the dawn of the 1990s.

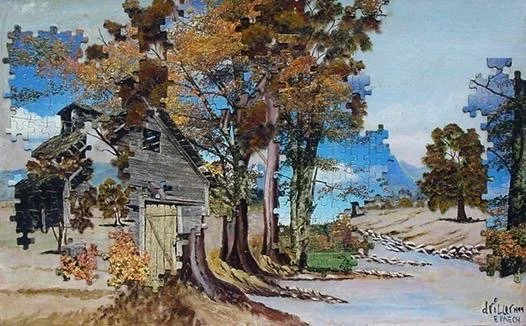

Shed Daub (1999)

Jigsaw intervention on original landscape painting

A foundational work in the emergence of Daubism, Shed Daub marks Driller Jet Armstrong’s first use of jigsaw puzzle fragments as a material and conceptual intervention into a pre-existing landscape. Rather than simply overwriting the colonial pastoral scene, Armstrong destabilises it from within, allowing pieces of the image to dislodge, drift, and fracture across the picture plane.

The jigsaw form operates on two simultaneous registers.

On the surface level, it is a direct physical disruption of the inherited European landscape tradition—an image long treated as complete, fixed, and authoritative. By inserting puzzle pieces, Armstrong reveals the landscape as constructed, contingent, and capable of being taken apart.

At a deeper level, the puzzle piece becomes a metaphor for the search for meaning within an artwork. The viewer is invited into an active process of assembly and interpretation, confronted with a picture that refuses to fully resolve. The missing pieces gesture toward cultural gaps, forgotten histories, and the impossibility of reconstituting a landscape without acknowledging what has been removed or obscured.

In this sense, Shed Daub is not merely a formal experiment—it is a philosophical turning point. The work inaugurates Armstrong’s ongoing project of “changing the landscape,” not only visually but conceptually, by demonstrating that meaning itself is a puzzle assembled from fragments, erasures, inheritances, and interventions.

Daubist Portrait of Max Harris (2009)

Gel transfer on original landscape painting (artist unknown), sourced portrait by Sidney Nolan (reverse image)

Daubist Portrait of Max Harris marks a pivotal moment in the evolution of Daubism — a point where the movement’s core strategies of appropriation, inversion, and recontextualisation expanded into portraiture and cultural memory itself.

In this work, Driller Jet Armstrong takes Sidney Nolan’s iconic portrait of Max Harris — the incendiary editor, poet, and enfant terrible of Australian modernism — and literally reverses it, both visually and conceptually. Through a delicate gel-transfer, Nolan’s image is lifted from its original context and re-embedded into an anonymous, sentimental landscape painting: the very type of generic Australiana that Harris himself spent much of his career challenging.

The result is a ghostly, semi-transparent Harris staring back at the viewer from within a borrowed landscape — not quite settled, not quite belonging, caught between artistic lineages. Armstrong allows the underpainting to bleed through the portrait, as if the land itself is reclaiming, revising, or resisting the introduction of this modernist figure.

This process embodies a new chapter in Daubist methodology:

1. Reversal as Critique

By reversing Nolan’s image, Armstrong destabilises authorship and authority. The act symbolically “turns around” the legacy of modernism, inviting the viewer to reconsider who frames Australian art history — and from what direction.

2. Gel Transfer as Archaeology

Unlike paint applied atop the surface, gel transfer embeds the appropriated image within the substrate of the older landscape. This creates a visual palimpsest: a dialogue between eras, intentions, and ideologies, compressed into a single pictorial plane.

3. Portraiture Meets Landscape

Where early Daubist works intervened in landscapes through symbols, figures, and cultural signifiers, this work introduces an individual into the terrain — placing Max Harris himself inside the picturesque conventions he raged against.

It becomes both homage and disruption.

4. A New Way of Making a New Work From an Old One

Here, Daubism extends beyond simply “altering” found paintings; it begins to hybridise entire genres. Armstrong fuses the postmodern act of appropriation with the tactile intimacy of analogue technique, producing a work that is neither portrait nor landscape but a new species altogether.

In its layered complexity, Daubist Portrait of Max Harris crystallises the movement’s essential question:

How can we re-author Australian art history using the very materials that built it?

Ghost Girls (2010)

Gel transfer (appropriated from Picasso) on original Australian landscape

Ghost Girls marks a pivotal moment in the Daubist evolution—one in which the act of appropriation becomes not merely a visual intervention, but a haunting. Here, two figures lifted from Picasso’s repertoire—faces and bodies once bound to European Modernism—are gel-transferred into the Australian bush, where they appear as spectral presences, half-formed and dissolving into gum-trunks, creek reflections, and ochre earth.

Rather than sitting comfortably within the borrowed pastoral, these girls seem dislocated, untethered, almost returnedrather than placed. Their translucency reads as both apparition and erasure: a reminder of the countless young lives disrupted or displaced throughout Australia’s colonial history, and a commentary on how European art traditions were imposed across Indigenous land, culture, and visual memory.

The work operates simultaneously on two registers:

– as Daubism, it fuses multiple art histories into a single contested surface, creating an image that neither the original painter nor Picasso could ever have authored;

– as cultural critique, it exposes the lingering ghosts of imported aesthetics and the stories overlooked by the great Western canon.

In Ghost Girls, the Australian landscape does not merely host the figures—it absorbs them, questions them, and ultimately transforms them. The result is a quietly powerful apparition: a scene where the past is visible but no longer authoritative, where borrowed icons become fragile, fading visitors in a much older Country.

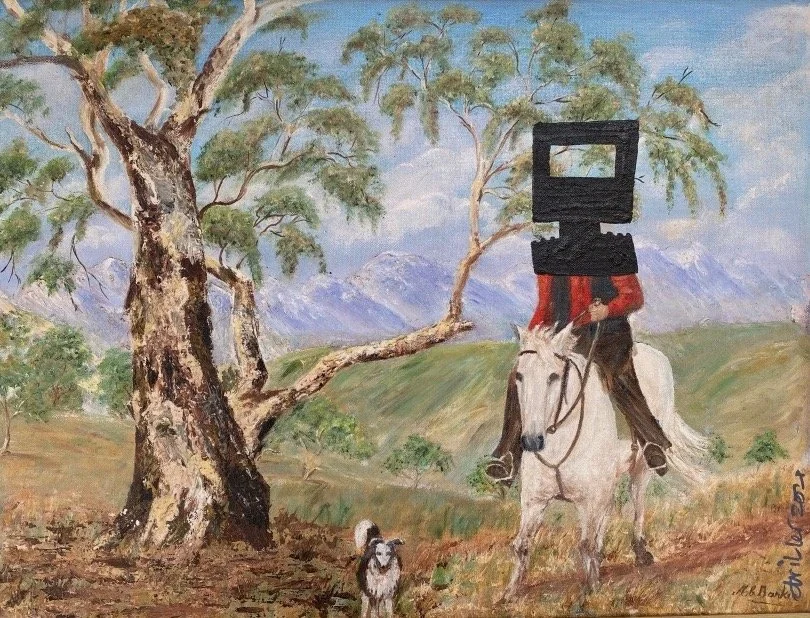

Ned on Horseback (2021)

acrylic on original landscape painting

In “Ned on Horseback”, Armstrong resurrects Sidney Nolan’s most recognisable silhouette — the iron-helmeted outlaw — and drops him, without ceremony, into the calm, romanticised pastoral vision of an anonymous Australian landscape painter. The result is both jarring and inevitable: Nolan’s modernist myth collides with the colonial idyll that originally produced the Kelly legend.

Here, Nolan’s square-headed outlaw no longer rides through expressionist scrub but into the decorative, settler-fantasy bushland typical of mid-century amateur painting. By grafting the iconic Ned Kelly mask directly onto an existing landscape, Armstrong performs a double appropriation: he borrows from Nolan, who himself borrowed from the myths of frontier violence, and inserts that image into a substrate soaked in colonial nostalgia.

The work extends the core Daubist principle — that new meaning is generated only by intervening on an already-existing artwork. Armstrong treats the borrowed landscape as both stage and accomplice, allowing a figure from Australia’s modernist canon to rupture the serene fiction of pastoral innocence. The Kelly helmet becomes a cultural glitch, a hard geometric interruption that exposes how myths are constructed, repeated, and repurposed across generations.

By merging Nolan’s outlaw with a thrift-store painting of rural harmony, Armstrong reminds viewers that national identity is never fixed — it’s layered, stolen, repainted and reinscribed, again and again. This Ned is not the hero or the villain; he is simply evidence of how images travel, accumulate meaning, and refuse to die.

NED DAUB 2018

The first realisation of the Daubist motif as a repeatable, transferable form.

This work marks a turning point in the evolution of Daubism. It was here—overlaying a stark, graphic figure onto an inherited Australian landscape—that the artist first recognised the radical potential of a repeating motif: a single, iconic form capable of being imposed onto any pre-existing painting while remaining entirely itself.

The revelation was deceptively simple:

the motif does not change—only the landscape beneath it does.

Each new background alters the emotional charge, historical weight, and visual tension of the figure, pulling the viewer into a shifting conversation between eras, authors, and aesthetics. This unlocked an entirely new methodology within Daubism—an approach later expanded through the felt unicorns, whale forms and other recurring symbols.

In this moment, Daubism became not just an act of appropriation, but a system:

a way of testing how an unchanging emblem behaves when dropped into new cultural, stylistic, and emotional terrain.

This work is the seed from which an entire vocabulary of repeated Daubist iconography grew.

Whale Watching I (2017)

Mixed media on found maritime painting

In Whale Watching I, Armstrong extends the Daubist principle of the repeatable motif—first crystallised in the Ned Kelly series—into a new marine vernacular. The giant black whale, a simplified and almost monolithic form, is dropped unapologetically onto an existing seascape, overwhelming the genteel maritime drama with a single, assertive gesture. Like the Ned helmet, the whale motif becomes a portable device: an image that can be applied to any pre-existing painting, its meaning shaped entirely by the landscape it interrupts.

Here, the original scene of boats battling a restless sea is abruptly recontextualised. The whale’s vast silhouette, matte and impenetrable, functions as both subject and void—part creature, part censor bar, part horizon. Its single inset “eye” reads like a portal, a witness, or a point of entry into the painting’s submerged narrative. The result is disarmingly literal: whale watching becomes the viewer watching the whale, and the whale—by sheer scale—watching everything.

By reusing a fixed motif across multiple appropriated paintings, Armstrong tests how repetition destabilises authorship. The whale hovers between menace and play, between symbol and stamp, between ecological reminder and mischievous artistic intervention. It is a continuation of Daubism’s central proposition: alter the foreground and the entire meaning of the inherited image shifts—sometimes subtly, sometimes violently, but always irreversibly.

Felt Me Up Daub (2009)

Felt additions on original landscape painting

In Felt Me Up Daub, Driller Jet Armstrong turns the polite Australian pastoral into a playground of cheerful vandalism. The genteel gum trees and distant hills—painted with all the earnest tranquillity of a second-hand-shop landscape—are abruptly invaded by felt.

Not just felt, but children’s craft felt: a cowboy with a toy gun, a lopsided pony, and the unmistakable aesthetic of a kindergarten collage.

Armstrong deliberately weaponises innocence.

The felt figures—soft, bright, and absurd—smother the colonial imaginary with the language of play. The work announces a key shift in Daubism: the introduction of non-paint materials as a way to overwrite inherited images without competing with them. Felt becomes a disarming force, a comic intervention, and a conceptual sledgehammer.

The result is a landscape that no longer behaves.

It becomes a stage set, a puppet theatre, a place where adult mythologies collapse under the weight of childish cut-outs.

This work marks one of the earliest examples of Armstrong’s “superimpositional” method:

the repeated insertion of a foreign motif—here, felt characters—onto any traditional painting, transforming the original without erasing it.

In true Daubist fashion, the felt refuses to apologise. It simply sits there—smiling, goofy, defiant—rewriting Australian art history one fuzzy cowboy at a time.

Ned 24 (2024) — Text

Gel transfer on found landscape painting with dotted perimeter.

Ned 24 marks a late, sharpened turn in Armstrong’s ongoing dialogue with the Australian myth-machine of Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly. Rather than painting the iconic helmet anew, Armstrong lifts Nolan’s imagery through gel-transfer — a ghostly importation that behaves less like quotation and more like cultural haunting.

Set against the soft pastoral calm of the original 20th-century landscape, the Ned figure materialises as a spectral intrusion: half-opaque, half-eroded, a presence that refuses to fully settle into the borrowed environment. The dotted border — a recurring Daubist device — acts like a ceremonial threshold, framing the friction between two pictorial worlds while refusing to let the viewer forget the painting’s hybrid construction.

In this work, Armstrong positions Ned not as hero, villain, or nationalist mascot, but as artifact — an image endlessly recycled in service of identity, rebellion, and mythology. Here, Ned becomes a fragile transfer, barely adhered, a reminder that the stories Australians cling to are themselves unstable layers pressed onto older, dissonant histories.

Ned 24 is less about Kelly the man and more about Kelly the motif: endlessly repeated, transplanted, eroded, and recharged. It is Daubism as cultural archaeology — excavating the images Australians inherit, the landscapes they obscure, and the myths that refuse to die.

Unicorn by the Sea (2015)

Felt figure on original landscape painting

A sombre, windswept seascape—grey sky, drifting reeds, gulls suspended in unsettled air—serves as the stage for an intervention straight from the height of 2015 pop-culture: the glitter-era unicorn. In the mid-2010s the unicorn was everywhere—Instagram filters, novelty stationery, ironic T-shirts, rainbow lattes—an emblem of mass-produced whimsy and digitally amplified optimism.

By affixing a small felt unicorn from a children’s game onto a moody, traditional coastal painting, Driller Jet Armstrong enacts a sharp Daubist collision. The unicorn becomes a recurring Armstrong motif precisely because of its power to instantly hijack visual hierarchy. With one playful insertion, the original painting is pushed into the background—still present, still respected, but radically recontextualised.

The result is both absurd and poignant: a symbol of pop-zeitgeist fantasy wandering into a landscape too serious for it, creating an emotional and conceptual dissonance. As always in Armstrong’s practice, the “daub” does not erase—it reveals. The original coastal scene becomes a foil, a quiet counterpoint to the loud cultural noise of the moment.

A 2015 unicorn at full cultural saturation, dropped into a lonely shore to remind us how easily fantasy rewrites the world around it.

Spirits in the Landscape (2005)

Acrylic on found landscape painting with appropriated rock-art figures

In Spirits in the Landscape, Driller Jet Armstrong overlays a rural settler painting with bold, graphic figures adapted from Aboriginal rock art, creating a deliberate collision between two incompatible visual regimes. The soft pastoral lull of the inherited landscape—an idealised cottage, a tidy horizon, an untroubled sky—is abruptly interrupted by ancient presences whose visual language far predates the colonial gaze.

The work stages a temporal rupture: the “original” painting becomes the most recent layer in a much older cultural continuum. Armstrong’s figures operate not as decoration but as assertions of sovereignty, embodiments of custodial knowledge re-entering a landscape from which they were once pictorially erased. Their placement over the domestic, settler-era cottage reconfigures the power dynamic—the background becomes the intrusion, while the rock-art forms reclaim the foreground.

As with much early Daubist work, appropriation here is both critique and homage. Armstrong’s intervention exposes how landscape painting in Australia has historically omitted Indigenous presence, and uses the act of “daubing” to reinsert what was always already there. The result is a work that vibrates between beauty and disruption, humour and seriousness—an image where spirits, once silenced, stand unapologetically in the centre of the frame.

SUICIDE NOTE ON CHARLES FRYDRYCH LANDSCAPE (1992)

oil on original landscape painting

One of the earliest and most confrontational works in the Daubist canon, Suicide Note on Charles Fridrych Landscapemarks a pivotal moment in the movement’s formation: the collision of pastoral sentimentality with raw emotional truth.

Across a serene, quintessentially Australian landscape by Charles Fridrych, Armstrong scrawls “goodbye cruel world” in urgent crimson—an inscription that feels at once juvenile, theatrical, and devastatingly sincere. The gesture is deliberately excessive: a defacement that refuses politeness, a refusal to “respect” the original in any conventional sense. Instead, Armstrong exposes the emotional vacuum at the heart of inherited Australian art traditions, laying bare the psychological rupture beneath their sunlit veneers.

Here, the landscape becomes not a place of comfort but a stage for existential crisis. The text destabilises the image, rupturing its pictorial calm with a declaration that is part graffiti, part cry for help, part performance. It prefigures Armstrong’s lifelong interrogation of authorship, ownership, and the fragile boundaries between reverence and violation.

More than an act of vandalism, the work is an early Daubist manifesto:

the belief that new meaning must be carved—violently if necessary—from the old.

Daubist Corgi with Queen (1992)

Cut-up and reassembled Charles Bannon landscape painting; acrylic on found canvas

In Daubism Corgi with Queen, Armstrong pushes early Daubist strategies to an almost Cubist extreme. A once-placid Charles Bannon landscape is meticulously cut apart, reordered, rotated, and reassembled into a hybrid figure: part monarch, part corgi, part rupture in the colonial imaginary. The original painting—once a stable depiction of an Australian idyll—becomes raw material to be sliced open and rebuilt into a new political body.

The work marks a decisive moment in the evolution of Daubism: the shift from simple over-painting into full deconstruction and reconstruction. Instead of merely “intervening” on the original, Armstrong dismantles its pictorial authority altogether, reorganising the very structure of the landscape into a figure whose fractured anatomy exposes the instability of inherited cultural narratives.

Simultaneously playful and unsettling, Daubism Corgi with Queen treats the landscape as both puzzle and protest—an act of regicide by collage, where the sovereign image is dethroned and recomposed under the artist’s rule. It stands as an early and radical articulation of Daubism’s foundational provocation: that every image is provisional, and every picture can be re-written.

The New Shore (2018)

Painted additions to an original landscape painting

“The New Shore” marks one of the most visually dramatic and politically charged moments in the evolution of Daubism. Driller Jet Armstrong overlays a genteel, anonymous landscape with an expanse of dense, engulfing blackness and a violently saturated field of red — a chromatic rupture that overwhelms the inherited calm of the original painting.

Against this destabilised ground, the small boats and their figures persist, suspended between two worlds: the inherited and the imposed, the picturesque and the obliterated. The dotted boundary — a recurring Daubist device — suggests both incision and repair, a suture line between histories that cannot fully meet.

The blood-red shoreline reads simultaneously as warning, memory, and future terrain. It evokes massacres, displacement, ecological collapse, and the ongoing violence of settler narratives embedded in banal landscape painting. Yet the boats drift toward this red zone as if toward a destination they cannot help repeating — a metaphor for Australia’s ongoing attempts to navigate its colonial legacy without truly confronting it.

In The New Shore, Armstrong forces the viewer into the disquieting space between image and intervention. The work insists that landscapes are never neutral: they are battlegrounds, burial grounds, and political fictions — and Daubism’s role is to make those fictions visible.

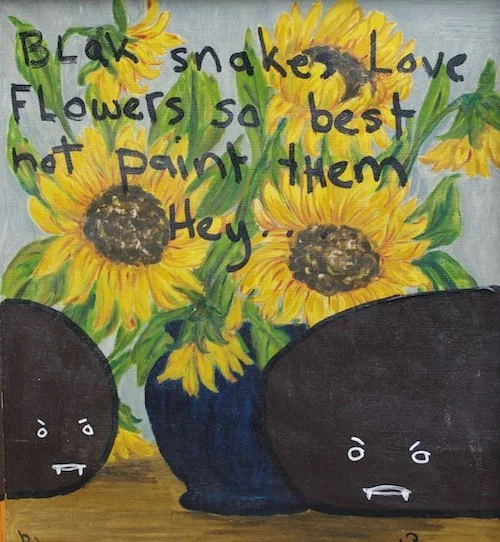

Blak Snakes Love Flowers (2011)

Painted text and character overlays on an anonymous still-life

In Blak Snakes Love Flowers, Armstrong detonates the genteel stability of the traditional still-life—a genre historically obsessed with purity, beauty, and order—by allowing his cartoon-like “blak snakes” to literally speak back. Their warning (“best not paint them, hey…”) functions as both a mischievous punchline and a cutting meta-critique of artistic entitlement.

The work folds together multiple registers of “appropriation”:

the still-life tradition, long associated with colonial importation of European aesthetics,

the hand-written interruption that refuses to behave like a caption,

and the Daubist creatures who emerge as protectors, critics, and cheeky agents of disruption.

These figures—simultaneously cute, irritated, and sentient—stage an argument about custodianship. Who has the right to depict? Who defends the subject? And what happens when the depicted world talks back?

Here the flowers are no longer passive objects. They become the centre of a territorial dispute, a site where Armstrong’s invented creatures petition for care, autonomy, and respect. The humour operates as camouflage for a deeper ethical gesture: an insistence that painting—and the histories it carries—is never neutral.

Like much of Armstrong’s early 2010s practice, the work is a declaration that Daubism is not vandalism but a counter-narrative: a world where voices previously flattened into background finally get to answer back.